Daniel Patrick Moynihan, ambassador, senator, sociologist, and itinerant American intellectual, born in 1927 wrote the report “The Negro Family: The Case for National Action.” In the report, Moynihan intended to outline how years of oppression have left the black male with out proper opportunities to be the head of a household. He argues that years of mistreatment, lacking employment, out of wedlock births have the of the black American family in a dangerous state. His idea is that through government programs like better education, work training programs, more black in the military, the black man can emerge from this state of despair to one of equity. However, the report was misinterpreted by those who heard about it and didn’t read it. It was used as a tool to justify disregarding the plight of the black family rather than to rally support. Now, 50 years later, we have more divided society, one where:

The United States now accounts for less than 5 percent of the world’s inhabitants—and about 25 percent of its incarcerated inhabitants. In 2000, one in 10 black males between the ages of 20 and 40 was incarcerated—10 times the rate of their white peers.

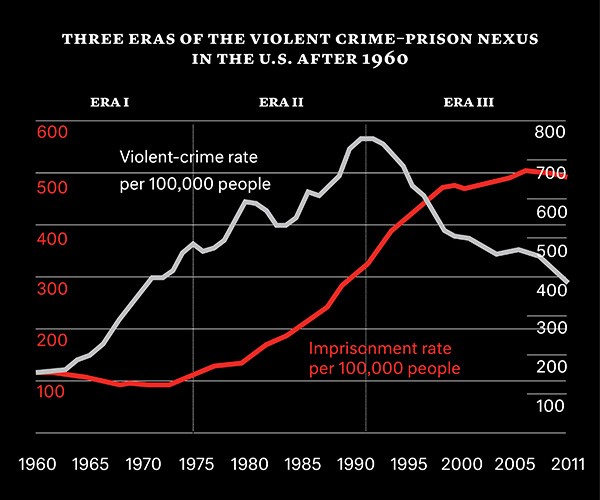

“From the mid-1970s to the mid-’80s, America’s incarceration rate doubled, from about 150 people per 100,000 to about 300 per 100,000. From the mid-’80s to the mid-’90s, it doubled again. By 2007, it had reached a historic high of 767 people per 100,000, before registering a modest decline to 707 people per 100,000 in 2012. In absolute terms, America’s prison and jail population from 1970 until today has increased sevenfold, from some 300,000 people to 2.2 million. The United States now accounts for less than 5 percent of the world’s inhabitants—and about 25 percent of its incarcerated inhabitants. In 2000, one in 10 black males between the ages of 20 and 40 was incarcerated—10 times the rate of their white peers. In 2010, a third of all black male high-school dropouts between the ages of 20 and 39 were imprisoned, compared with only 13 percent of their white peers.”

At a cost of $80 billion a year, American correctional facilities are a social-service program—providing health care, meals, and shelter for a whole class of people.

As the civil-rights movement wound down, Moynihan looked out and saw a black population reeling under the effects of 350 years of bondage and plunder. He believed that these effects could be addressed through state action. They were—through the mass incarceration of millions of black people.

America’s closest to-scale competitor is Russia—and with an autocratic Vladimir Putin locking up about 450 people per 100,000, compared with our 700 or so, it isn’t much of a competition. China has about four times America’s population, but American jails and prisons hold half a million more people. “In short,” an authoritative report issued last year by the National Research Council concluded, “the current U.S. rate of incarceration is unprecedented by both historical and comparative standards.”

******

Fathers should be supported by public policy, in the form of jobs funded by the government. Moynihan believed that unemployment, specifically male unemployment, was the biggest impediment to the social mobility of the poor. He was, it might be said, a conservative radical who disdained service programs such as Head Start and traditional welfare programs such as Aid to Families With Dependent Children, and instead imagined a broad national program that subsidized families through jobs programs for men and a guaranteed minimum income for every family.

Influenced by the civil-rights movement, Moynihan focused on the black family. He believed that an undue optimism about the pending passage of civil-rights legislation was obscuring a pressing problem: a deficit of employed black men of strong character. He believed that this deficit went a long way toward explaining the African American community’s relative poverty. Moynihan began searching for a way to press the point within the Johnson administration. “I felt I had to write a paper about the Negro family,” Moynihan later recalled, “to explain to the fellows how there was a problem more difficult than they knew.” In March of 1965, Moynihan printed up 100 copies of a report he and a small staff had labored over for only a few months.

“The Negro Family” argued that the federal government was underestimating the damage done to black families by “three centuries of sometimes unimaginable mistreatment” as well as a “racist virus in the American blood stream,” which would continue to plague blacks in the future:

That price was clear to Moynihan. “The Negro family, battered and harassed by discrimination, injustice, and uprooting, is in the deepest trouble,” he wrote. “While many young Negroes are moving ahead to unprecedented levels of achievement, many more are falling further and further behind.” Out-of-wedlock births were on the rise, and with them, welfare dependency, while the unemployment rate among black men remained high. Moynihan believed that at the core of all these problems lay a black family structure mutated by white oppression:

In essence, the Negro community has been forced into a matriarchal structure which, because it is so out of line with the rest of the American society, seriously retards the progress of the group as a whole, and imposes a crushing burden on the Negro male and, in consequence, on a great many Negro women as well.

Moynihan believed this matriarchal structure robbed black men of their birthright—“The very essence of the male animal, from the bantam rooster to the four-star general, is to strut,” he wrote—and deformed the black family and, consequently, the black community. In what would become the most famous passage in the report, Moynihan equated the black community with a diseased patient:

In a word, most Negro youth are in danger of being caught up in the tangle of pathology that affects their world, and probably a majority are so entrapped. Many of those who escape do so for one generation only: as things now are, their children may have to run the gauntlet all over again. That is not the least vicious aspect of the world that white America has made for the Negro.

Despite its alarming predictions, “The Negro Family” was a curious government report in that it advocated no specific policies to address the crisis it described. This was intentional. Moynihan had lots of ideas about what government could do—provide a guaranteed minimum income, establish a government jobs program, bring more black men into the military, enable better access to birth control, integrate the suburbs—but none of these ideas made it into the report. “A series of recommendations was at first included, then left out,” Moynihan later recalled. “It would have got in the way of the attention-arousing argument that a crisis was coming and that family stability was the best measure of success or failure in dealing with it.”

*******

The press did not generally greet Johnson’s speech as a claim of white responsibility, but rather as a condemnation of “the failure of Negro family life,” as the journalist Mary McGrory put it. This interpretation was reinforced as second- and thirdhand accounts of the Moynihan Report, which had not been made public, began making the rounds. On August 18, the widely syndicated newspaper columnists Rowland Evans and Robert Novak wrote that Moynihan’s document had exposed “the breakdown of the Negro family,” with its high rates of “broken homes, illegitimacy, and female-oriented homes.” These dispatches fell on all-too-receptive ears. A week earlier, the drunk-driving arrest of Marquette Frye, an African American man in Los Angeles, had sparked six days of rioting in the city, which killed 34 people, injured 1,000 more, and caused tens of millions of dollars in property damage. Meanwhile, crime rates had begun to rise. People who read the newspapers but were not able to read the report could—and did—conclude that Johnson was conceding that no government effort could match the “tangle of pathology” that Moynihan had said beset the black family. Moynihan’s aim in writing “The Negro Family” had been to muster support for an all-out government assault on the structural social problems that held black families down. (“Family as an issue raised the possibility of enlisting the support of conservative groups for quite radical social programs,” he would later write.) Instead his report was portrayed as an argument for leaving the black family to fend for itself.

******

What caused this [mass incarceration rates]? Crime would seem the obvious culprit: Between 1963 and 1993, the murder rate doubled, the robbery rate quadrupled, and the aggravated-assault rate nearly quintupled. But the relationship between crime and incarceration is more discordant than it appears. Imprisonment rates actually fell from the 1960s through the early ’70s, even as violent crime increased. From the mid-’70s to the late ’80s, both imprisonment rates and violent-crime rates rose. Then, from the early ’90s to the present, violent-crime rates fell while imprisonment rates increased.

Examining a sample of states, Neal found that from 1985 to 2000, the likelihood of a long prison sentence nearly doubled for drug possession, tripled for drug trafficking, and quintupled for nonaggravated assault.

That explosion in rates and duration of imprisonment might be justified on grounds of cold pragmatism if a policy of mass incarceration actually caused crime to decline. Which is precisely what some politicians and policy makers of the tough-on-crime ’90s were claiming. “Ask many politicians, newspaper editors, or criminal justice ‘experts’ about our prisons, and you will hear that our problem is that we put too many people in prison,” a 1992 Justice Department report read. “The truth, however, is to the contrary; we are incarcerating too fewcriminals, and the public is suffering as a result.”

“If greatly increased severity of punishment and higher imprisonment rates caused American crime rates to fall after 1990,” the researchers Michael Tonry and David P. Farrington have written, then “what caused the Canadian rates to fall?” The riddle is not particular to North America. In the latter half of the 20th century, crime rose and then fell in Nordic countries as well. During the period of rising crime, incarceration rates held steady in Denmark, Norway, and Sweden—but declined in Finland. “If punishment affects crime, Finland’s crime rate should have shot up,” Tonry and Farrington write, but it did not. After studying California’s tough “Three Strikes and You’re Out” law—which mandated at least a 25-year sentence for a third “strikeable offense,” such as murder or robbery—researchers at UC Berkeley and the University of Sydney, in Australia, determined in 2001 that the law had reduced the rate of felony crime by no more than 2 percent. Bruce Western, a sociologist at Harvard and one of the leading academic experts on American incarceration, looked at the growth in state prisons in recent years and concluded that a 66 percent increase in the state prison population between 1993 and 2001 had reduced the rate of serious crime by a modest 2 to 5 percent—at a cost to taxpayers of $53 billion.

*****

The emergence of the carceral state has had far-reaching consequences for the economic viability of black families. Employment and poverty statistics traditionally omit the incarcerated from the official numbers. When Western recalculated the jobless rates for the year 2000 to include incarcerated young black men, he found that joblessness among all young black men went from 24 to 32 percent; among those who never went to college, it went from 30 to 42 percent. The upshot is stark. Even in the booming ’90s, when nearly every American demographic group improved its economic position, black men were left out. The illusion of wage and employment progress among African American males was made possible only through the erasure of the most vulnerable among them from the official statistics.

These consequences for black men have radiated out to their families. By 2000, more than 1 million black children had a father in jail or prison—and roughly half of those fathers were living in the same household as their kids when they were locked up. Paternal incarceration is associated with behavior problems and delinquency, especially among boys.

“More than half of fathers in state prison report being the primary breadwinner in their family,” the National Research Council report noted. Should the family attempt to stay together through incarceration, the loss of income only increases, as the mother must pay for phone time, travel costs for visits, and legal fees. The burden continues after the father returns home, because a criminal record tends to injure employment prospects. Through it all, the children suffer.

******

For instance, in the 1990s, South Carolina cut back on in-prison education, banned air conditioners, jettisoned televisions, and discontinued intramural sports. Over the next 10 years, Congress repeatedly attempted to pass a No Frills Prison Act, which would have granted extra funds to state correctional systems working to “prevent luxurious conditions in prisons.” A goal of this “penal harm” movement, one criminal-justice researcher wrote at the time, was to find “creative strategies to make offenders suffer.”

*******

When the doors finally close and one finds oneself facing banishment to the carceral state—the years, the walls, the rules, the guards, the inmates—reactions vary. Some experience an intense sickening feeling. Others, a strong desire to sleep. Visions of suicide. A deep shame. A rage directed toward guards and other inmates. Utter disbelief. The incarcerated attempt to hold on to family and old social ties through phone calls and visitations. At first, friends and family do their best to keep up. But phone calls to prison are expensive, and many prisons are located far from one’s hometown.

******

The carceral state has, in effect, become a credentialing institution as significant as the military, public schools, or universities—but the credentialing that prison or jail offers is negative. In her book, Marked: Race, Crime, and Finding Work in an Era of Mass Incarceration, Devah Pager, the Harvard sociologist, notes that most employers say that they would not hire a job applicant with a criminal record. “These employers appear less concerned about specific information conveyed by a criminal conviction and its bearing on a particular job,” Pager writes, “but rather view this credential as an indicator of general employability or trustworthiness.”

We also offer you another story on this topic. This from Radio Boston looks at safe towns and in 71 percent of teens self reported committed some illegal acts, but most are given warnings by police and punished by parents. Impoverished areas teens are treated differently. “There are troubled kids everywhere.” Kids in the juvenile justice system are primarily minorities.

<iframe width=”100%” height=”124″ scrolling=”no” frameborder=”no” src=”//embed.wbur.org/player/radioboston/2015/09/18/juvenile-crime-suburbia”></iframe>

Close to 150,000 kids in the US will spend time in a juvenile detention facility in any given year. Black inner city youth are almost five times more likely to be incarcerated than their white peers. But that’s not because kids in inner cities are more prone to crime, it’s because suburban communities deal with juvenile crime differently.

Northeastern University criminology professor Simon Singer says kids labeled as juvenile delinquents are in every neighborhood — regardless of a community’s affluence. And he says how a community handles delinquency will determine whether those young people become productive — or criminal — adults.

Professor Singer followed hundreds of teens in a community described as the safest city in America. What he found was that most of the young people in this so-called “safe” city committed crimes, but they did not end up in court — and they successfully transitioned into adulthood..