There’s talk of a coup in the Republican party, a contested convention hasn’t happened for decades and it doesn’t really seem like anyone knows what the rule would be. Trump is threatening the party with riots if they deny him the nomination. Clinton maybe the nominee for the Dems but Sanders has made a big point, though there is little chance still for victory for those feeling the Burn, their voices have been heard.

What is a contested convention?

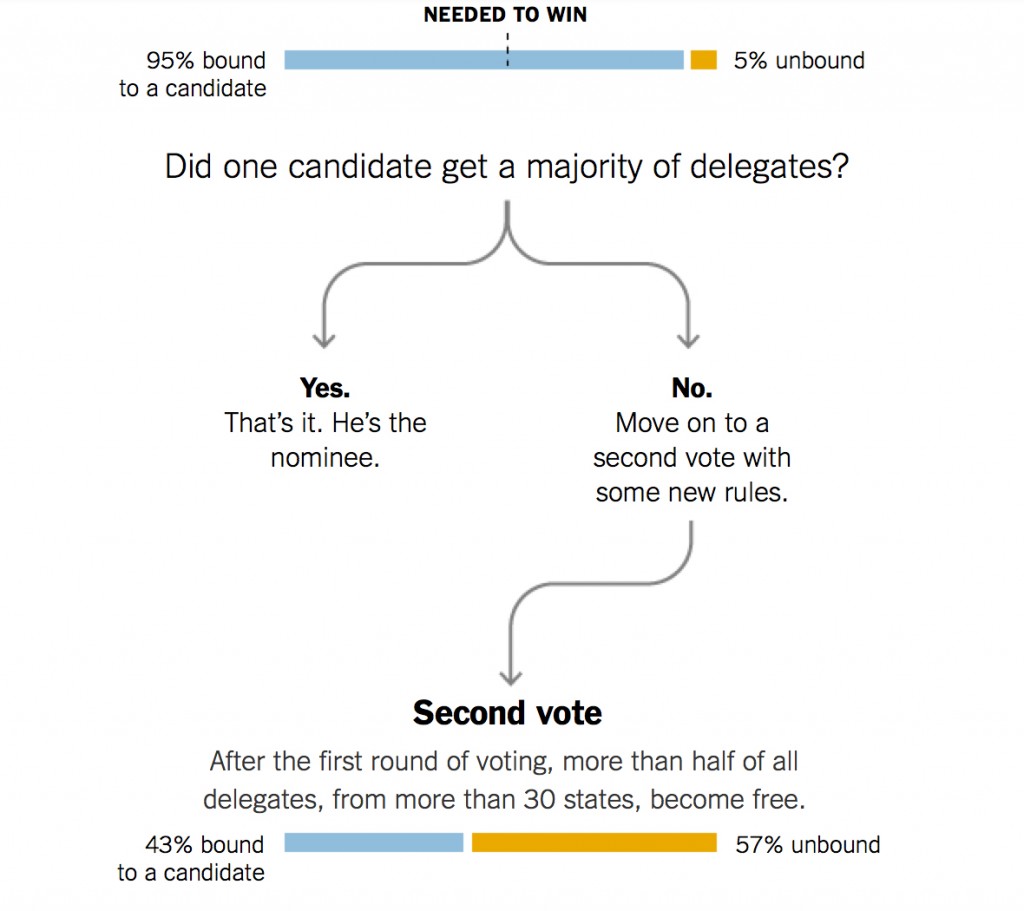

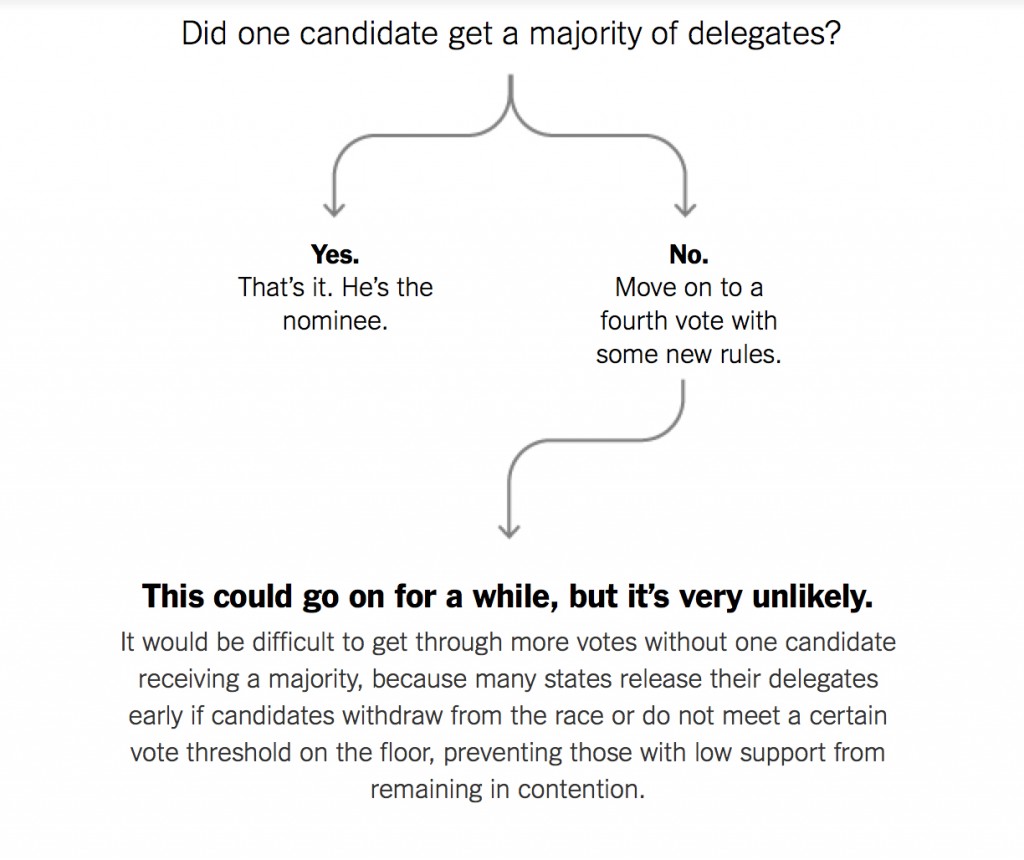

A contested convention happens when a candidate fails to secure the nomination before the July meeting. Most states “bind” their delegates. This means if a candidate wins the primary the delegate must vote for that person at the national convention. At least 5 percent of delegates are not bound.

The exception is if the candidate does not receive the majority of votes, 1237, then the delegates are free to vote however they want at the convention. The Republican party is hoping this happens. Trump is promising it will not happen

From The New York Times:

There’s also a prereq called the Eight State’s Rule:

Currently, in addition to securing a majority of delegates, a candidate is required to win more than 50 percent of delegates in at least eight states to secure the nomination. Mr. Trump has already done so in five.

However, this rule, or any other, could be changed before the voting begins, putting candidates who do not win a majority in eight states into contention.

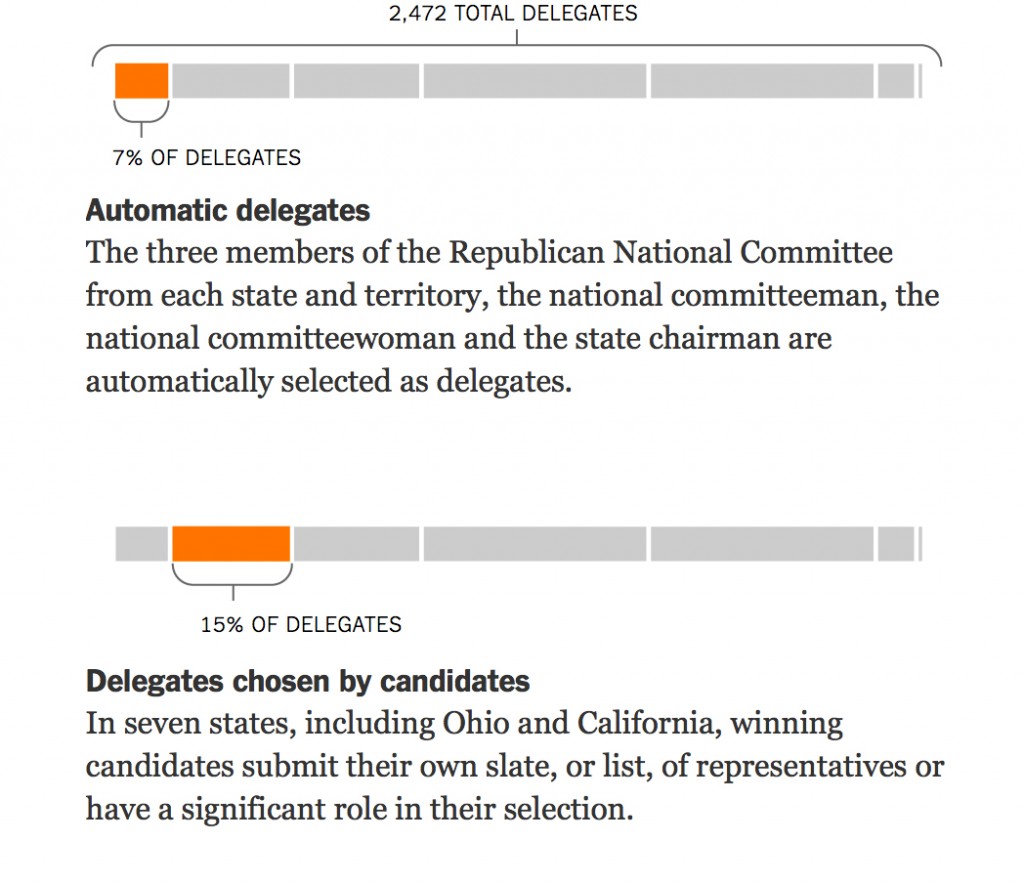

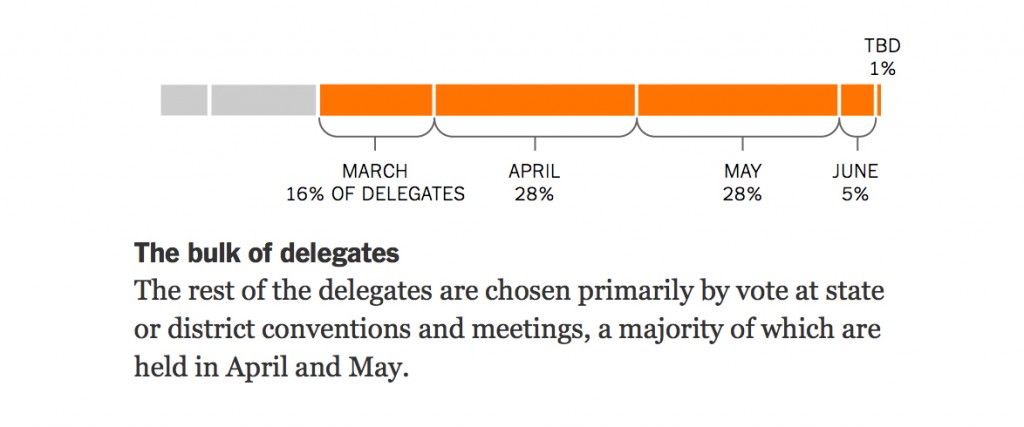

Who Gets To Be A Delegate?

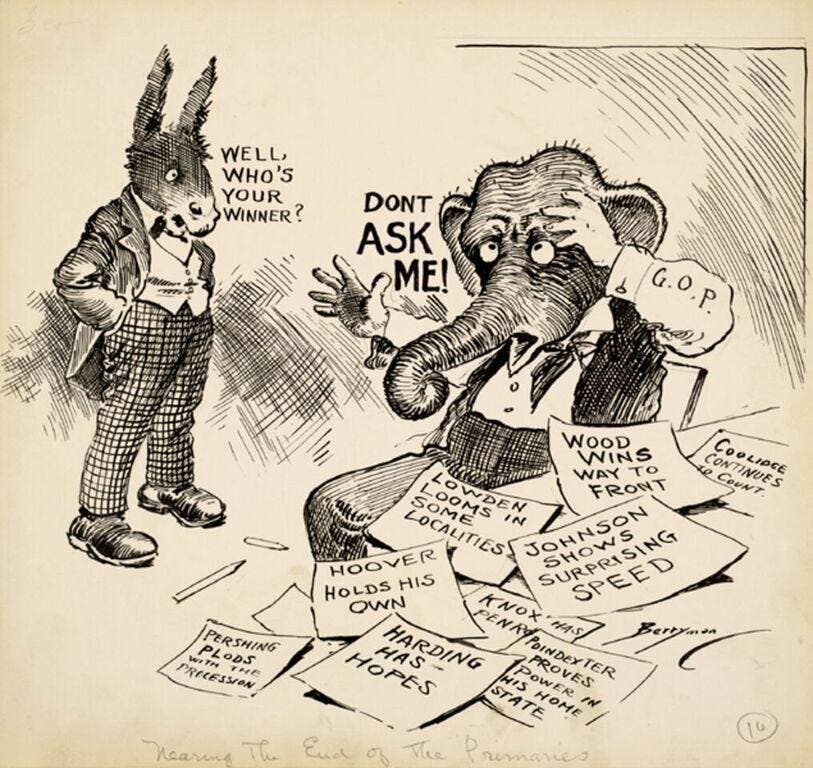

We love looking at the historical context for these kinds of issues, and this topic is ripe with history. Below is an excerpt on brokered conventions in U.S. history.

Following the riotous 1968 Democratic convention in Chicago, sweeping electoral reforms handed more control over the presidential nomination process to the voters. Since then, there hasn’t been a brokered, or also called contested, convention.

That’s because the reforms removed the brokers — strong party leaders, typically in cities, who designed nomination tickets and handed their decisions down to delegates.

“Now, there are no strong party leaders,” said L. Sandy Maisel, professor of government at Colby College. “Can you imagine the Trump delegates listening to Mitt Romney? Or anyone else? We will have a free-for-all convention, and that is very different from when party leaders met in smoke-filled rooms and set the course of the nation.”

The legend of the original smoke-filled room originated in (where else?) Chicago, at the Blackstone Hotel. The story goes that after the 1920 Republican convention deadlocked over more than a dozen candidates, a group of powerful, stogie-puffing GOP party bosses sat up late into the night in Room 404, eventually settling on darkhorse Warren G. Harding.

That kind of deal-making often occurred hand-in-hand with multiple voting ballots cast by delegates in the convention hall, usually at the behest of the party bosses back in the smoke-filled rooms. It took the Democrats an agonizingly slow 44 ballots in San Francisco in 1920 to finally choose Ohio’s governor as their nominee. In 1924, the Democrats chose John W. Davis of New York as their nominee on the 103rd attempt, after 16 days.

After covering the 1924 proceedings for the Baltimore Evening Sun, H.L. Mencken wrote:

There is something about a national convention that makes it as fascinating as a revival or a hanging. It is vulgar, it is ugly, it is stupid, it is tedious, it is hard upon both the higher cerebral centers and the gluteus maximus, and yet it is somehow charming. One sits through long sessions wishing heartily that all the delegates and alternates were dead and in hell — and then suddenly there comes a show so gaudy and hilarious, so melodramatic and obscene, unimaginably exhilarating and preposterous that one lives a gorgeous year in an hour.

Brokered conventions occur when no candidate has won a majority of the delegates before the party’s nominating convention. If, by July 18, when the GOP convention begins in Cleveland, none of the Republican candidates has collected 1,237 delegates, the 2,472 delegates will choose the nominee by ballot.

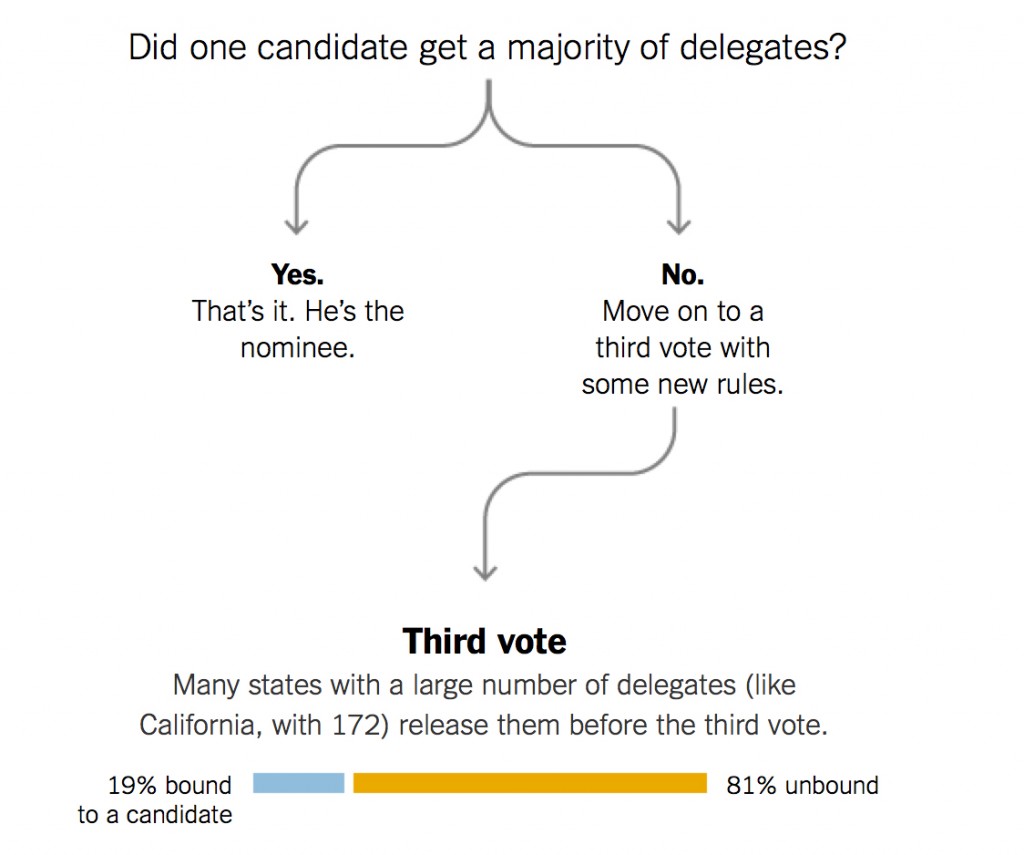

If no nominee is selected on the first ballot, all bets are off. Some delegates will be unbound from the candidates they were sent to Cleveland to vote for. And with no party leaders to answer to, many will simply make up their own minds about where to point their vote.

“Until the 1940s, the behavior of individual delegates from one ballot to the next was often a product of a strategy pursued by the political leaders they were beholden to,” said David Hopkins, a professor of political science at Boston College. If Republicans “end up with a brokered convention [in July], and no nominee arises on first ballot, it’s a lot less clear how the delegates will behave after that first ballot, and who will influence them, and who can speak for them and who can make deals on their behalf.”

The most recent brokered conventions were in 1948 for the Republicans, and in 1952 for the Democrats. But it was the riots in Chicago’s Grant Park — across the street from the Blackstone Hotel — in 1968 that led to the reforms GOP leaders will have to contend with in July.

That year, anti-war Democrats believed they had performed well in the primaries, especially with Minnesota Senator Eugene McCarthy. Vice President Hubert Humphrey announced his candidacy, but didn’t compete in any of the party’s primaries. His nomination angered an already enraged anti-war contingent who felt party bosses chose a candidate who hadn’t faced voters and didn’t represent the will of the average Democrat.

The reforms that took place before the 1972 elections broadened participation in the nomination process, taking power out of the hands of party bosses. In some ways, four decades later, GOP leaders will have to deal with the ripple effects of those reforms if they want to block a Trump nomination.

In such a scenario, “presumably no one will have the majority of delegates, but someone will have more than the rest, and if that’s Trump, even if he doesn’t have an overall majority, he can claim he’s closer than anyone else,” said Hopkins. “If he argues that he came in first in the official process, and is therefore the only legitimate choice at the convention, the GOP leadership will have to reckon with that in way it didn’t have to worry about in old days.”

So, decades after giving more power to the people, the GOP may feel the need to take that power back, in order to save the party from itself. The alternative, if matters proceed to a second ballot: bedlam.