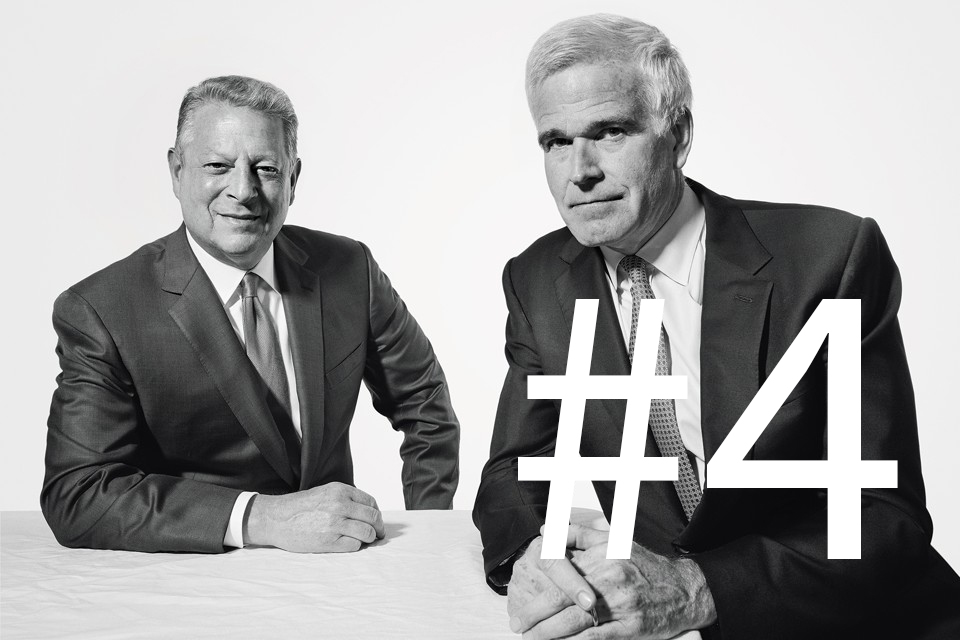

Al Gore, the former United States Veep, faced a kind of senioritis when the Supreme Court ruled his popular vote victory wasn’t leading to a comfy bed at 1600 Pennsylvania Avenue.He didn’t know what he wanted to do when he grew up. So he aligned himself with the companies he felt offered future promise — Google and Apple. Though he’s often mocked, Gore’s kicked some ass since then. His net worth was valued between $1-$2million, according to financial disclosure documents, when he ran for President. Just 15 years later he’s rumorred to be worth hundreds of millions of dollars…

An Inconvenient Truth, the book, the movie, the audiobook won him the #1 international bestseller spot, 2 Oscars, and a Grammy respectively, oh an a Nobel Peace Prize. He got a “Several hundred million” bucks for the sale of the TV channel, Current TV, he started with a partner and sold in 2103 to Al Jazeera. He’s a partner at Kliener Perkins and on the board of Apple, but Gore says the big bucks come from his investment firm with a sustainable strategy.

The Atlantic: “Al Gore’s Green Technology Investment Strategy”

The most sweeping way to describe this undertaking is as a demonstration of a new version of capitalism, one that will shift the incentives of financial and business operations to reduce the environmental, social, political, and long-term economic damage being caused by unsustainable commercial excesses. What this means in practical terms is that Gore and his Generation colleagues have done the theoretically impossible: Over the past decade, they have made more money, in the Darwinian competition of international finance, by applying an environmentally conscious model of “sustainable” investing than have most fund managers who were guided by a straight-ahead pursuit of profit at any environmental or social price.

********

Gore is obviously delighted to discuss the implications of his firm’s success. “I wanted us to start talking when the five-year returns were in, but cooler heads persuaded me that we should wait until now,” he told me. But he says he is not doing so to attract more business. The minimum investment Generation will accept in its main fund is $3 million, and even then individuals must show they have total assets many times that large to be “qualified investors.” And besides, its most successful fund is now closed to new investment. Instead he and his colleagues are aiming at a small audience within the financial world that steers the flow of capital, and at the political authorities that set the rules for the financial system. “It turns out that in capitalism, the people with the real influence are the ones with capital!,” Gore told me during one of our talks this year. The message he hopes Generation’s record will call attention to is one the world’s investors can’t ignore: They can make more money if they change their practices in a way that will, at the same time, also reduce the environmental and social damage modern capitalism can do.

*********

During that tumultuous time, from the summer of 2005 through this past June, the MSCI World Index, a widely accepted measure of global stock-market performance, showed an overall average growth rate of 7 percent a year. According to Mercer, a prominent London-based analytical firm, the average pre-fee return for the global-equity managers it surveys was 7.7 percent. This meant that after fees, which average about 70 “basis points” (or seven-tenths of 1 percent), the returns an average professional money manager could produce barely kept up with plain old low-cost, passive index funds. Individual investors have heard this message (“You can’t beat the market, so why try?”) for years, from index-investing firms like Vanguard. The Mercer analysis says that it applies even to the big-endowment pros.

But through that same period, according to Mercer, the average return for Generation’s global-equity fund, in which nearly all its assets are invested, was 12.1 percent a year, or more than 500 basis points above the MSCI index’s growth rate. Of the more than 200 global-equity managers in the survey, Generation’s 10-year average ranked as No. 2. In addition to being nearly the highest-returning fund, Generation’s global-equity fund was among the least volatile.

Read the full story on The Atlantic site

“We are making the case for long-term greed,” David Blood told me in July. Blood is Generation’s senior partner and on-scene leader at its headquarters in London. The formal name for the concept he and Gore are advancing is sustainable capitalism, which sounds both more familiar and less hard-edged than what I understand to be the real underlying idea. The idea is that if some tenets of “long term” and “value based” investing are extended to include the environmental and social ramifications of corporate activity, the result can be better financial performance, rather than returns that are “nearly as good” or “worth it when you think of the social benefits.”

I asked David Rubenstein, the billionaire co-founder and co-CEO of the Carlyle Group, the private-equity firm, what he thought of Generation’s aspirations and its business model. “The general theory in investing is that the highest returns go to those who are unencumbered by sustainability or other environmental and social constraints,” he said. Generation’s “pitch that the conventional wisdom is wrong may be right; their record would be a good barometer.”

“They are indeed unusual, in applying such a comprehensive sustainability perspective,” Dominic Barton, the global head of McKinsey, said when I asked him about Generation’s approach. “They have created a real demonstration vehicle for the idea that if you are broad-minded and care about externalities, you can actually add shareholder value. Many people have talked about this, but now they have done it.” The economist Laura Tyson, of UC Berkeley, who is part of Generation’s unpaid advisory board, said that Gore and Blood were “genuine pioneers” in showing the practicality of their investment approach. “When they started, very few people believed that a sustainability strategy could offer competitive returns,” she told me. “Their hypothesis has been borne out by their results.”

*******