Electra, Texas—1985

SHE WAS A PRETTY GIRL, thin, with a spray of pale freckles across her face and light brown hair that curled just above her shoulders. The librarian at the high school called her “a quiet-type person,” the kind of student who yes-ma’amed and no-ma’amed her teachers. She played on the tennis team, practicing with an old wooden racket on a crack-lined court behind the school. In the afternoons she waitressed at the Whistle Stop, the local drive-in hamburger restaurant, jumping up on the running boards of the pickup trucks so she could hear better when the drivers placed their orders.

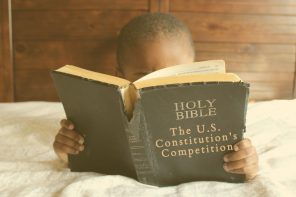

Her name was Treva Throneberry, and just about everybody in that two-stoplight North Texas oil town knew her by sight. She was never unhappy, people said. She never complained. She always greeted her customers with a shy smile, even when she had to walk out to their cars on winter days when the northers came whipping off the plains, swirling ribbons of dust down the street. During her breaks, she’d sit at a back table and read from her red Bible that zipped open and shut.

There were times, the townspeople would later say, when they did wonder about the girl. No one had actually seen her do anything that could be defined, really, as crazy. But people noticed that she would occasionally get a vacant look in her blue eyes. One day at school she drew a picture of a young girl standing under a leafless tree, her face blue, the sun black. One Sunday at the Pentecostal church she stumbled to the front altar, fell to her knees, and began telling Jesus that she didn’t deserve to live. And then there was that day when Treva’s young niece J’Lisha, who was staying at the Throneberry home, told people that Treva had shaken her awake the previous night and whispered that a man was outside their room with a gun—which turned out to be not true at all.

But surely, everyone in town said, all teenage girls go through phases. They get overly emotional every now and then. Treva was going to turn out just fine. She didn’t even drink or smoke cigarettes like some of the other girls in town.

Then, that December, just as the Electra High School Tigers were headed toward their first state football championship and the town was feeling a rare surge of pride, Treva, who was sixteen years old, stopped working at the Whistle Stop. She stopped coming to school. “She disappeared,” a former classmate said. “And nobody knew where she went.”

Vancouver, Washington—1997

THE NEW GIRL ARRIVED AT EVERGREEN High School wearing loose bib overalls, a T-shirt, and tennis shoes, and her hair was braided in pigtails. She was fuller-figured than most teenage girls, wide-hipped, but she had an appealing, slightly lopsided smile and a childlike voice tinged with a Southern drawl. She was carrying a graphite tennis racket and a Bible.

Her name, she told school officials, was Brianna Stewart. She was sixteen years old, she said, and for almost a year she had been living in Portland, Oregon, just across the Columbia River from Vancouver, walking the streets during the day and sleeping in grim youth shelters at night. She started attending services at Vancouver’s charismatic Glad Tidings Church, where she met a young couple who took her into their home after hearing her testimony. The couple, who had accompanied Brianna to school that morning, said that she was full of potential, determined to succeed—and that all she needed was a chance to get over her past.

“What is your past?” asked one of the school’s counselors, Greg Merrill.

For a moment Brianna said nothing, as if she was trying to maintain her composure. Then she told Merrill that she had been raised just outside Mobile, Alabama, by her mother and her Navajo stepfather, a sheriff’s deputy. Brianna said that when she was a child, her mother had been murdered, and after that she lived with her stepfather. At about the age of thirteen, she ran away, hitchhiking from state to state. Because Brianna remembered her mother telling her that her real father lived somewhere in the Northwest, she had come to the area hoping that she could find clues to her past.

It was the most unusual case Merrill had ever heard in his thirty years of counseling students. When he asked about her education, she told him she had only been home schooled, but she promised she would be a good student. “I’ve never had a normal life,” she said. “That’s all I want—to be a normal teenager like everyone else.”

She was enrolled in the tenth grade at the 1,900-student school. One of her first classes was Algebra I. She walked in and was given a seat toward the back, where she pulled out a notebook and began listening intently to the teacher. Then she glanced over at the boy sitting next to her.

“Hi,” said Ken Dunn, who couldn’t stop smiling at her.

She giggled shyly. “Hi,” she said. “I’m Brianna. I’m new here.”

Electra, Texas—1985

IT DIDN’T TAKE LONG FOR the rumor to spread through town that Treva Throneberry had last been seen down at the police station, where she had given a statement claiming that her daddy, holding a gun in his hand, had raped her. She added that her mother had only laughed when she found out what had happened.

A stunned police officer called child welfare, which quickly sent a social worker to Electra to whisk Treva away, and a judge entered emergency protection orders temporarily preventing Treva’s parents from seeing their daughter or even finding out where she was. Soon, Electra was buzzing: Was it possible that Carl Throneberry had raped his own daughter?

Carl and his wife, Patsy, were known as good country people. They lived in a small frame home decorated with a photo of John Wayne on one wall and a rug that depicted the Last Supper on another. Carl was a big, lumbering man, a truck driver in the oil fields. He had met Patsy in the early fifties at a soda fountain in Oklahoma, and after a few weeks of courting, they had driven to the A&P supermarket in Wichita Falls, where the butcher, who was also a preacher, had wiped his hands on his apron, pulled out a small pocket Bible, and performed their wedding ceremony out in the A&P parking lot while the couple sat holding hands in the back seat of Carl’s Chevy.

Yes, Carl admitted, he sometimes had trouble making ends meet, but he had always made sure his children—one son and four daughters, of whom Treva was the youngest—were well fed and dressed properly for school. In fact, Carl said, his older brother Billy Ray often dropped by to give the four Throneberry girls presents. After the older girls had left home, Billy Ray especially doted on Treva, bringing her candy bars, buying her clothes from the dollar store, and taking her on drives in his car.

In court Carl and Patsy insisted that Treva had made up the entire story, and their attorney went so far as to demand that Treva be given a lie-detector test. Treva’s sisters also gave affidavits saying they too believed that their father was innocent.

If anyone had raped Treva, Carl told police officers and social workers, it was one of those fanatical members of Electra’s Pentecostal church. He knew for a fact, he said, that they had been trying to brainwash her into becoming a missionary. The church members, in turn, said they had only been trying to help a young girl who was obviously in great distress. They said that in the weeks leading up to her rape allegation, Treva had been telling them that she was scared of being at her home and that she had been slipping out at night to sleep in an abandoned house next door or even on a pew at the church itself. What was also perplexing to social workers was Treva’s behavior at the foster home in Wichita Falls where she had been taken. Her foster mother, Sharon Gentry, a middle school science teacher, said that she would often find Treva at night curled in a fetal position in the corner of her bedroom, the bedcovers pulled over her head. On other nights Gentry would find her banging her head against the wall, murmuring in her sleep, “Please don’t hurt me. I’ll be a good girl.”

Like so many who had known Treva, Gentry was touched by the girl’s gentleness. Around the house, she was soft-spoken and exceedingly polite. She began attending Wichita Falls High School, where she developed a reputation as a diligent, thoughtful student. She regularly read her Bible, and she wrote soulful teenage poetry in her notebook. One poem began:

Raining tears, flowing down my face

Yours forever, a lost case

No one cares or sees you fall

No one hears you when you call.

As the weeks passed, however, Treva started to leave disturbing handwritten notes on the ironing board for Gentry. “Sometimes I wish I were dead,” she wrote in one note. “Sometimes I don’t. Life seems impossible and death seems eternal. I will have no life after death.” She came out of her bedroom one morning and told Gentry that she had been dreaming about shooting herself. In the dream, she said, she could see the bullet entering her head. She later told her a story about how she had been kidnapped in Electra and taken blindfolded by members of a satanic cult to an abandoned oil field, where she was tied to a stake. People in black robes danced around her, she said, then slit the throats of black cats and dogs and forced her to drink their blood.

In May 1986 Treva went to see her counselor at Wichita Falls High School and said in an eerily calm voice that she was thinking about jumping off the third floor of the building to kill herself. Police officers sped to the school, handcuffed Treva, and drove her to the old, redbrick Wichita Falls State Hospital at the edge of the city. There she spent long periods of time by herself, sitting in the dayroom of the adolescent unit, looking out through large windows on the neatly mowed lawns. According to hospital reports, she was often seen crying. She rarely ate. Her face was blank, her cheeks sunken, her hair flat. Doctors and therapists arrived to give her various tests, including the Woodcock-Johnson Psychoeducational Battery. They sat beside her and asked if she felt detached, if she felt hostile, if she felt withdrawn, if she felt lonely. They prescribed Xanax, for anxiety, and Trilafon, which was designed to combat what they called thought disorders, and Tofranil, an antidepressant. They put her in a weekly group-therapy session, where she and other adolescents sat in a circle on vinyl-covered chairs.

But she said little. She did write a few sad letters to Gentry and a boy from Wichita Falls High School who had once taken her on a date to Six Flags Over Texas. “I feel like a living robot,” she wrote to him. “I walk when they say walk. I sit when they say sit. I do everything they say because I have to. I can’t take it anymore. I have to die.”

Needing to put something in their reports, the baffled doctors described Treva’s condition as a “characterological disorder.” “She’s kind of quiet and secretive and she may have a personality problem,” wrote one therapist. Perhaps to get a better clue of what had happened to her, staffers finally arranged for her to meet with her parents, who had been coming to the hospital demanding to see her. (The district attorney’s office ultimately dismissed the sexual assault charges against Carl, saying there was no evidence to prosecute.) Treva sat with Carl and Patsy in the presence of a social worker and a therapist as her parents told her to admit that she had been lying about the rape. Treva rose and said that they were the ones who were the liars, that they didn’t love her, and then she announced that she had nothing more to say and that she wished to return to her room.

Vancouver, Washington—1997

BRIANNA STEWART SEEMED SO GRATEFUL just to have the chance to be at Evergreen High. Each morning, she rode a city bus to the school, her backpack crammed with her textbooks and her Bible. Like a lot of students she had trouble with algebra, but she shone in English. She was able to quote entire passages of Macbeth from memory, the Shakespeare play the sophomore class was required to read, and for extra credit she wrote poems and stories, including one about a little girl who had only imaginary friends as playmates.

Almost every day she came to school in the same outfit—overalls, a T-shirt, and tennis shoes—and she wore pigtails, a serious teenage fashion faux pas. One afternoon a classmate named Cheyanne McKay asked Brianna if she would like to go to the mall with a group of other girls. On the way there Cheyanne cranked up the stereo, and she and a couple of other girls in the car started dancing. When Brianna tried to dance along, she moved in jerky, arrhythmic ways, as if she had never danced to that kind of music in her life.

To most of the Evergreen kids, Brianna was the classic teenage wallflower. But for Ken Dunn, an amiable sandy-haired sophomore, Brianna was unlike any other girl he had ever known. “I like the way she walks, and I really like the way she talks,” he told his friends, referring to her Southern accent. In algebra he began imitating the way she wrote sevens on her homework, adding a short horizontal line through the middle of the number. He escorted her from class to class, and he smiled encouragingly at her during tennis practice, despite the fact that she was easily the worst player on the girls’ team. He spent much of his time helping her work on her lines for her drama class. Brianna was a hopelessly awkward actress, yet she still tried out for all the school plays. Perhaps out of pity, the drama teacher put her in the chorus of the school’s production of Man of La Mancha, where she moved leadenly across the stage, smiling bravely, making stilted gestures, and nearly colliding with the other performers.

Soon, Ken and Brianna were swapping flirtatious notes. (“Hi!” Brianna wrote. “What’s up? I know—the great blue sky!!! . . . You’re the best guy I’ve ever known as a friend. You’re more than that to me . . . Class of 2000 rules!”) In his 1978 brown El Camino, known around school as the Turd Tank, Ken began taking Brianna on little dates—to the bargain stores in downtown Vancouver, to the roller rink, and to the mall, where they sat in the food court and talked. He attended services with her at the Glad Tidings Church and went with her to the Thursday-night youth group meetings, where she often gave her testimony. He was amazed at the amount of Scripture Brianna knew. He told his parents that she must have studied the Bible for years—for years!

Initially, Brianna told Ken only a few details about her past. But sitting at the food court one day, Brianna took a deep breath and told Ken stories she said she hadn’t told anyone. She said she had watched her stepfather stab her mother to death and carry the body away. He then made tapes of himself and his friends raping her, which he sold on the black market. When she became pregnant at the age of eleven or twelve, he pushed her down a flight of stairs to force her to miscarry. She went to the police station to turn him in, but no one would believe her. They called her stepfather to come pick her up, which is why she knew she had to flee.

And there was one more thing, Brianna said, her voice softer than ever. Earlier that summer, just before coming to Evergreen, she had gotten to know a security guard who worked in downtown Vancouver. One day while the two of them were sitting in his car, she said, he pulled down his pants, then pulled down her pants, and forced her to have intercourse. “He raped me. He raped me. He raped me,” she repeated over and over, tears streaming down her face. “I wanted to kill myself. I began to think about standing on an overpass and jumping off.”

“Here was this beautiful girl who had been forced to endure unimaginable atrocities,” Ken would later say. “And yet here she was at Evergreen, wanting to make something of herself in life. I wanted to help. I wanted to make her happy. I wanted her to know that someone cared for her.”

He took her to the school’s Sadie Hawkins dance, where they dressed in matching blue overalls and crimson shirts. When the disc jockey played Shania Twain’s “You’re Still the One,” he escorted her onto the dance floor, looked her in the eyes, and said, “I love you.”

“I love you too,” Brianna replied.

Ken pushed her hair back and kissed her on the mouth. Then he kissed her again.

“I was sixteen, and she was sixteen,” he recalled. “It was the perfect teenage romance. I couldn’t imagine that anything could go wrong.”

Wichita Falls, Texas—1986

AFTER TREVA HAD SPENT FIVE MONTHS at the state hospital, the doctors declared that she was no longer suicidal or severely depressed. Her biggest issue, said her adolescent-unit therapist, was that she was “unpredictable.” She was discharged in October 1986, yet even then no one was sure what to do with her. Treva begged her social workers not to return her to her parents, which suited Carl and Patsy just fine. They didn’t want her home, they said, until she recanted her rape story.

It was finally decided that Treva would be sent to the Lena Pope Home, the Fort Worth residential treatment center for troubled adolescents. There, counselors came up with a therapeutic plan to improve her skills in “self-confidence” and “to develop and maintain interpersonal relationships.” She was enrolled at nearby Arlington Heights High School so that she could finish her senior year.

In June 1987 she wore a beautiful blue graduation gown as she walked across the stage to receive her diploma, smiling politely at the principal. Treva had just turned eighteen, and by law she could no longer be under state juvenile supervision. She was completely on her own. When her counselors at Lena Pope asked what she would do next, she said she planned to apply to a Bible college that didn’t require an SAT test. “All I want is to be and to feel normal,” she wrote to one of her social workers before she left state care. “I want to live life, but I want it to be normal and most of all, I want to live a normal life.”

Treva did return to Electra for a couple of days. Although she refused to go to her parents’ home, she visited with her three older sisters— Carlene, Kim, and Sue. “Treva, honey, what you said about Daddy is still breaking his heart,” said Carlene. “You need to go apologize.”

Treva did not respond. She kept her eyes locked on the floor.

Each of the sisters asked Treva what was bothering her, but the truth was that they didn’t really need to be told. They knew why Treva didn’t want to return to that house. They knew what she had endured there—because they had endured it themselves. When they were children, they too had lain awake in their own beds at night, praying that he would not come to touch them.

“He” was not their dad. “He” was their father’s older brother, Uncle Billy Ray. He was a Vietnam veteran, divorced and a heavy drinker, and he often stayed at the Throneberry home. Sometimes he’d ask one of the girls if she wanted to go with him to the store. “Go on,” their dad would say. He adored his older brother. “Let Billy Ray buy you something nice.”

According to the statements that Carlene, Kim, and Sue would give years later, long after Billy Ray had died, they didn’t just receive cute presents from their uncle. On the nights that he stayed at their home, he’d slip out of his bed and tiptoe to where his nieces were sleeping, moving from one bed to another, running his hands restlessly, endlessly, over their bellies, thighs, and bottoms. He’d put his hands up their shirts to feel their undeveloped breasts, and he’d put them down their panties to feel between their legs. His breathing would get faster and faster. “Keep your mouth shut,” he’d say, his breath stinking with liquor. Sometimes, he’d grab them for just a few seconds; other times, for minutes. No matter how long it lasted, the girls would shut their eyes, their teeth clenched, and they would make no sound at all—no scream, not even a whimper.

“We didn’t know what to do,” Carlene recalled. “We were just children—uneducated, small-town girls. I know you’re not going to understand this, but those times were different. We were too scared to say anything because we thought people would make us feel ashamed and tell us it was our fault. We had tried to let Momma and Daddy know what he was doing—at least we thought we had. But we didn’t come out and say anything outright because Billy Ray had told us that if we ever did, he’d have Momma and Daddy killed, and then he’d have us all to himself. What were we supposed to do? We thought, and I know this sounds so terrible, that this was the way things worked, that this was how everyone lived.”

As they got older, Carlene, Kim, and Sue still didn’t say anything—”We had been trained from an early age not to talk about it, not even to each other,” said Sue—but they did everything to keep their distance from Billy Ray. They worked double shifts at their waitressing jobs. Sue ran away once, and when she was caught in the Panhandle town of Childress, she was too scared to tell her parents why she had left. All three of them got married as teenagers so they could live in their own homes.

Which meant that Treva was left alone, the sweetest and the quietest of all the Throneberry girls—and the favorite of Uncle Billy Ray. Each of the older Throneberry girls believe that Billy Ray turned into an even greater predator with Treva. When Sue came back to the house one day, she saw little Treva sitting on Billy Ray’s lap. His hips were squirming back and forth, his hand underneath her shirt. Sue froze, torn between the desire to race forward and grab her little sister and the fear she had of her uncle.

When Carlene was sixteen and already married, she asked Treva, who was then ten, if she needed any help with Billy Ray. “You know what I mean, don’t you?” Carlene asked. But Treva said she liked Billy Ray’s presents. “She still didn’t understand what was happening to her,” Carlene said. “I’ll never get over the shame that I didn’t do something for her right then.” Carlene paused. “I’ll never get over that shame.”

When Treva reached the age of sixteen and accused her father of rape, the sisters assumed that she too had finally reached the point where she had to make her own escape. “She knew child welfare would get her out of there if she accused Daddy,” Carlene said. “I think she was just like us, too scared about what people might say or believe if she told the truth.”

The sisters also assumed that she would handle the rest of her life the way they had handled theirs—suffering in silence, praying to God that they could get through a day without the memories returning. But as they talked to her, they began to wonder if Treva’s escape had come too late. They listened in disbelief as Treva began to tell them stories that seemed, well, crazy. She told Kim the story about being kidnapped by a satanic cult, which forced her to drink blood and participate in infant sacrifices.

“Treva, why are you talking like that?” Kim asked.

But she could not tell if Treva was listening to her. That vacant look had returned to Treva’s eyes, as if she were somewhere else entirely.

A day after her arrival in Electra, Treva left. She never did go to college. She lived briefly in the Fort Worth area with a woman who was raising three children, and then reportedly she went to live at a YWCA. On one occasion Sharon Gentry received a collect phone call from Treva, who said she was working at a run-down motel in Arlington. She called again and said she was living on the streets. And then she disappeared.

“We never really did look too hard for her,” said Sue. “It wasn’t that we didn’t want to see her. We figured that she wanted to get away, to get a new start. At least that’s what we hoped she was doing—that she was alive somewhere, doing her best.”

Vancouver, Washington—1998

BY THE FALL OF 1998, HER junior year, Brianna Stewart had become a well-known figure at Evergreen High. Most of the kids had heard the stories of her tormented childhood. They had learned that she had courageously gone to the Vancouver police to file rape charges against the security guard, who had pleaded guilty to “communicating with a minor for immoral purposes.” Whenever students would see her in her oversized overalls and her pigtails, they’d say, “Hi, Bri”—she preferred the shortened version of her name, pronounced “Bree”—and she’d shyly smile back and tell them to have a nice day.

Brianna said her goal in life was to become a lawyer, focusing on children’s issues. She spent her free time in the library reading books about law or researching elaborate reports she would turn in to her teachers bearing the titles “Society’s Missing Youth,” “Child Abuse,” and “Adjustive Behaviors.” For an English class she wrote a poignant short story titled “Betrayed” about a girl named Jessica who has no idea where she came from. In it the police and the FBI conduct a DNA test that proves that Jessica was abducted as a child.

The story was not unlike Brianna’s own search for her past. As she told almost anyone who would listen, she desperately needed a Social Security number that identified her as Brianna Stewart. If she could just get one, then she would be able to move on with her life—obtain a driver’s license, apply for college, find a job. The problem was that the federal government would not issue her a new Social Security number unless she could track down her birth certificate or find her real father—or at least find some evidence to show that he, and she, existed.

What complicated the search was that Brianna was hazy about many parts of her past. The mental-health professionals in Vancouver who had interviewed her believed she suffered from amnesia or some sort of post-traumatic stress syndrome. Brianna, for instance, was not even sure what her real name was. She knew only that when she was a little girl her stepfather had started calling her Brianna, which he had told her meant “Bright Eyes” in Navajo. “I probably wasn’t always Brianna Stewart,” she told a sympathetic reporter from a weekly Portland newspaper who interviewed her in 1999. “I may not know who I was before I was three.” But then she added adamantly, “I do know who I am now.”

Numerous people were more than willing to help her. A state social worker conducted exhaustive governmental record searches looking for any evidence of Brianna, her mother, or the man she said was her stepfather. A staffer from Indian Health Services, who had been unable to get Brianna off his mind since meeting her, scoured national databases of missing children and even asked her to give blood in hopes of finding a DNA match. She reportedly asked an FBI agent in Portland to investigate whether she was the victim of an unsolved kidnapping in Salt Lake City and visited a Montana sheriff’s office to find out if she was a girl who went missing in 1983.

Everyone came up empty-handed. Undeterred, Brianna took time off from school in January 2000 and rode the bus to Daphne, Alabama, where she said she had been raised. A police detective from Daphne spent several days driving her around, hoping she would see something that would jog her memory. She saw a swing set at a park that she remembered playing on. She saw a table at a McDonald’s where she believed she had once sat. Nevertheless, no one could find any evidence that she had ever lived there.

One possible clue came when she visited a dentist in Portland. The dentist later told a social worker that he was surprised to notice that Brianna’s wisdom teeth had been extracted and that the scars had healed—highly unusual for a sixteen-year-old girl. When the social worker asked Brianna about the dentist’s statement, she responded with a blistering five-page, single-spaced letter criticizing those who would doubt her story. “My word means much to me,” she wrote, “and when I give my word that I am doing and being as honest and upfront as I can with the information about myself, I mean it.”

When Brianna talked to Ken about the dentist’s story one afternoon while they cruised around in the Turd Tank, he found himself, to his astonishment, under attack when he asked if there might be anything to what the dentist was saying. “How dare you think that I’m not sixteen?” Brianna said, furious. “How dare you even ask that? How can you even say you love me?”

Ken tried to put the confrontation out of his mind. He knew deep down that she loved him. Just a few weeks earlier she had worn a dress to the homecoming dance that his mother had made using yards of the most expensive gold lamé that she could find at Fabric Depot. To show that he still loved her, he bought her a sterling silver ring for Christmas, the inside of which was engraved with her favorite line from the new Romeo and Juliet movie, starring Leonardo DiCaprio: “I love thee.”

But at the end of their junior year, something happened that devastated him. By then Brianna was staying with the Gambetta family, whose son was good friends with Ken. (She had told him that she needed a new place to live because the church families could no longer afford to keep her.) The Gambettas had been treating her like a daughter, giving her the spare bedroom, where she could put her tennis posters on the wall, and providing her with an allowance of $10 a week. Everything, in fact, seemed idyllic—until Brianna called the police in May 1999 and said that David Gambetta, the father of the household, had been spying on her. She said he had put miniature cameras in the light fixtures in her room and was making videotapes of her as she undressed.

After a quick investigation the police decided that the accusations were groundless, and the Gambettas ordered Brianna to move out. Yet Brianna, who soon found new lodging with the mother of a police officer, kept insisting she was telling the truth. For the first time, Ken didn’t believe what she was saying. In fact, he began thinking back on all the dramatic stories she had told him. “My God,” he said to one of his friends, “what if Brianna has been making everything up?”as the years passed and nothing more was heard from Treva Throneberry, many people in town assumed she had been killed. Carl and Patsy maintained a $3,000 burial insurance policy on their daughter. In 1993 a rumor swept through Electra that Treva had died in the fire at the Branch Davidian compound near Waco. Sharon Gentry even sent Treva’s dental records to the authorities investigating the fire to see if one of the burned bodies might be Treva.

Treva was not there. But in the little town of Corvallis, Oregon, two thousand miles away, there was a teenager named Keili T. Throneberry Smitt working at a McDonald’s and staying with a family she had met at a church. She told people she preferred the name Keili Smitt. In fact, she went to court in Corvallis to change her name legally to Keili Smitt because she said she was hiding from her father, who lived in Dallas. She told Corvallis police officers that he had already found her once in Oregon, forced her into his car, and raped her.

But the police could never find Keili’s father, and eventually she disappeared. The next summer she surfaced in Portland, telling the police there that she was on the run from her sexually abusive father. This time she said that her father was a Portland police officer. Once again, an investigation was begun, and once again, Keili disappeared.

She reappeared in the summer of 1994 in the town of Coeur d’Alene, Idaho, where she told the police her name was Cara Leanna Davis. She said her mother had been murdered and her father, a police officer, had been a member of a satanic cult and had repeatedly raped her. After two months in Coeur d’Alene, she vanished. Later that year she arrived in Plano, a suburb north of Dallas. She told rapt police officers and social workers that her name was Kara Williams, that she was sixteen years old, and that she had been born and raised in a satanic cult, where she had been taught that her destiny was to honor Satan and to die in a lake of fire. She said that many of the children she had grown up with had been sacrificed, stabbed to death with daggers. Her own mother had been murdered by her father, a cult leader who happened to be a police officer in Colleyville, another Dallas suburb. He also raped her repeatedly, she said, and at bedtime would force her to chant prayers to Lucifer.

One female detective was so determined to discover who had harmed Kara that she drove to Colleyville and asked the police chief if he knew of any officer who might have any kind of special interest in the study of satanic activities. A volunteer for a social-work agency took it upon herself to show Kara the outside world, taking her to malls and to Six Flags. Social workers shuttled her from various foster homes and youth shelters around the Dallas area, trying to find a place where she would feel safe. At one shelter she accused a young male staffer of sexually molesting her, which led her to be moved again. With each move she was enrolled in a new high school. In the spring of 1995 alone, Kara attended high schools in Sadler, Sherman, and Dallas, joining the tennis team at each new place. The Child Protective Services worker supervising Kara’s case, Susanne Arnold, went so far as to buy her a new tennis racket to help her play better.

But in September 1995 Arnold received a call at home from a staffer at the residential treatment center where Kara was staying. The staffer, who just happened to be from the little town of Electra, said, “Susanne, I think Kara is actually a twenty-six-year-old woman named Treva Throneberry.”

Days later Kara was confronted at the treatment center with records, photographs, and handwriting samples that proved her identity. Yet she confessed to nothing. Her protests were so adamant, and so tearful, that more than one person watching her came to the conclusion that she truly believed what she was saying. After a court hearing discharged her from government supervision, Arnold handed her a quarter and gave her the phone numbers for the state’s mental health office and for a homeless shelter. “Please get some help,” Arnold said. But as Kara got on an elevator, she told Arnold one last time that she was not Treva Throneberry, and she disappeared again.

In June 1996 a sixteen-year-old teenager named Emily Kharra Williams arrived in Asheville, North Carolina, where she told police officers she was on the run from a cult in Texas. In August 1996 a sixteen-year-old girl named Stephanie Williams came to Altoona, Pennsylvania, where she told the police she was on the run from her father in Memphis, Tennessee, who was involved in a cult and a child pornography ring. A social worker spotted a reference in the girl’s notebook to a Susanne Arnold in Texas, and some phone calls and records checks proved that the girl was Treva Throneberry. She was arrested and sent to jail for nine days for providing a false report to law enforcement. At one point an Altoona social worker called Carl and Patsy and asked them to speak to their daughter, to remind her who she was.

“Hi, baby,” said Carl. “It’s your daddy.”

“You sound like an awful nice man, and I wish you were my father, but you’re not,” Treva replied. “I’m not who you think I am.”

“Honey, you’ll be Treva Throneberry until the day you die,” Patsy said in a wobbly voice. “Now stop playing games.”

“Oh, no,” she said. “You got me mixed up with someone else. But someday I may just get that way to see you.”

And once again, after her release from the Altoona jail, she was on the road, making appearances in Louisiana, New Jersey, and Ohio, where she’d show up at youth shelters carrying some luggage, a teddy bear, a Bible, a flute with sheet music, and algebra homework. She kept reenacting the same scenario, looping back in time. She found her refuge in high school: eating cafeteria food, playing on the tennis team, studying Macbeth in English, and memorizing quadratic equations in algebra year after year after year. She kept trying to get back to the one place every teenager wants to leave.

Why? Why had Treva Throneberry used at least eighteen teenage aliases since the early nineties, and why had she spun such gruesomely outlandish tales? Was she nothing more than a con artist, pretending to be a downtrodden teenager to receive free foster care and a free education? Was she afflicted with what doctors call psychiatric Munchausen syndrome, in which she intentionally feigned intense emotional distress to receive extra attention?

Or was she slowly descending into an irreparable insanity, the likes of which no one had ever seen before? Was it indeed possible that by the time she entered Evergreen High School in 1997, she had completely forgotten the girl she had once been in 1985?

Vancouver, Washington—2000

IN JUNE 2000 BRIANNA STEWART WORE a beautiful green graduation gown as she walked across the stage to receive her diploma from Evergreen High School, where she earned a 2.33 grade point average. At a graduation party Ken Dunn approached her. Although he and Brianna had broken up after the Gambetta “hidden camera” episode, no one had ever affected him in the way she did. As the head-banger band Burner played in the background, the two talked about her plans to attend a community college in Vancouver. The financial aid office at the college would allow Brianna to enroll with a tuition scholarship despite the fact that she had no Social Security number. Ken, who would leave Vancouver for a job at Disney World that fall, said, “You’re going to do great, Brianna, and I mean it.”

She spent the summer of 2000 working as a volunteer answering phones for the Ralph Nader presidential campaign, but most of her time was devoted to getting a Social Security number. She wrote a six-page letter to the governor of Washington asking for help. She also enlisted the services of two lawyers—one in Portland and one in Vancouver, neither of whom knew what the other was doing. The attorney in Vancouver sued the state to force the Vital Records Office to issue Brianna a birth certificate. To support the claim, he provided letters from school officials, Brianna’s high school transcripts, her state picture identification, and medical statements about her mental health. The attorney in Portland chose to petition the federal government directly, asking it to issue Brianna a Social Security number. Before filing the petition, however, he had asked Brianna to submit to a fingerprint test just to make sure there was no chance she could be someone else.

Weeks later the Vancouver attorney was informed by a state deputy attorney general that the state would not oppose Brianna’s petition for a birth certificate. All Brianna would have to do was appear for a simple court hearing set for March 2001. Brianna’s three-year fight for an identity was finally over. She was about to officially become known as Brianna Stewart.

But on March 22, a week before the hearing, a Vancouver police detective arrested Brianna on charges of theft and perjury. He told her that she was a 31-year-old woman and that she had fraudulently received free foster care and free public education from the State of Washington. When Brianna told the detective that there had to be some mistake, he said that her fingerprints, which had been requested by her Portland attorney, had matched those of a woman from Altoona, Pennsylvania, by the name of Treva Throneberry.

Ken Dunn’s mother called him in Disney World with the news. He nearly dropped the phone. “Mom, I went to homecoming with a woman twelve years older than me,” he said. Most of the Evergreen kids were convinced that Brianna had brilliantly hoodwinked them all. They thought she had deliberately acted awkward in her drama class, where she received a D, and had lost all of her tennis matches against girls half her age as part of her plot to deceive. But others weren’t so sure about her motives. They were fascinated, for example, that she still couldn’t make an A in algebra despite fifteen years of high school. “It just goes to show you how algebra can really suck,” one girl said.

Just as curious was the reaction of the community itself. Although Clark County senior deputy prosecutor Michael Kinnie said that Treva needed to be treated as a common criminal—”What we are dealing with here is a woman who knows exactly what she’s doing,” he said—a writer for the Vancouver newspaper suggested that Treva’s behavior “doesn’t suggest maliciousness so much as misery.” As for Kinnie’s contention that Treva was dangerous—after all, a Vancouver security guard went to jail because of her accusation of rape—the writer reminded his readers that the security guard pleaded guilty. “Even though his record has since been cleared because no minor was actually involved,” the writer’s editorial pointed out, “he apparently thought there was, so he might not be without guilt himself.”

Letters to the editor from Vancouver’s citizens came in that favored Treva’s getting psychiatric help rather than being sent to prison. One angry writer said that the authorities were “spending far more taxpayer money through the legal system than Throneberry’s relatively harmless scam cost.”

There was an even greater outpouring of sympathy for Treva after her sisters told reporters about the sexual abuse she, and they, had suffered. “This case is not about fraud but about a tremendous emptiness, a need, a trauma very early in her life,” one of her court-appointed attorneys told reporters. If Treva was truly a con artist looking for financial gain, the attorney added, she could have picked a far better ruse than wandering the country as a homeless youth.

But for many, the greatest mystery about the story was why Treva Throneberry—after being caught in Plano, Texas, in 1995; Altoona, Pennsylvania, in 1996; and now Vancouver, Washington, in 2001—still refused to admit who she was. From her jail cell she declared in letters to the judge and in interviews with the news media that she had never before heard of Treva Throneberry. When her niece J’Lisha wrote her, she says that Treva responded with a letter of her own: “Dear J’Lisha Throneberry . . . I’m sorry to tell you this. I don’t know who you are.”

How much Treva actually remembered about her past had become a topic of enormous interest to psychiatrists, psychologists, and social workers. Some experts speculated that her past abuse from her uncle had been like a physical trauma, disconnecting memories in her brain. One professor of psychology said the abuse could have set off what is known as a “dissociative fugue,” a type of amnesia in which she didn’t know how she got where she was or why she was there. Others suggested she could have a multiple-personality disorder, in which she had created several personalities over the years to deal with her sexual abuse. A psychologist who had examined her for several days in 1995 when she was in Texas pretending to be Kara Williams was intrigued by her sincerity when she talked of satanic rituals and gang rape. “There was nothing in her behavior or presentation to suggest that she was knowingly misrepresenting the facts,” the psychologist had written in his report.

What baffled everyone in Vancouver was her decision to give her fingerprints to the attorney. If she had been thinking rationally, she would certainly have known that the fingerprints would link her to Altoona. It was equally odd that, after her arrest, she demanded that her DNA be compared with the DNA of Carl and Patsy Throneberry. She said that she was certain such a test would prove she was not their child. (The DNA tests showed a 99.93 percent likelihood that she was.) And why did she try so hard to get people to look into her past, to discover her real identity? If she was deliberately trying to con people, why would she set herself up to be discovered?

There was little in medical or psychological literature that came close to helping the experts understand what had happened to Treva. “If it is what people think—a woman needing to go back to a certain age and relive it again and again—then it would be one for the books,” said Kenneth Muscatel, a Seattle psychologist who had been hired by the court to examine Treva. “Here is a woman who invents stories to get the love and affection she had never known in her home, yet a woman so profoundly disturbed that she ends up turning on the very people who are trying to help her, accusing them of abuse.”

Other than J’Lisha, no one from Treva’s family tried to contact her after her arrest. Carl said he didn’t write Treva because he had dropped out of school in the sixth grade and didn’t know how to spell. He did want it known, however, that he was angry that “completely untrue stories” about Treva and his brother had made the newspapers. Patsy said she didn’t write because she was still hurt by the way Treva had turned her back on the family. She did say that she believed that Treva hadn’t forgotten about her entirely. At the funeral of her own mother, in 1998, Patsy said there was an elderly lady sitting at the back, wearing an old faded dress. The lady brushed against her as everyone was leaving the funeral parlor. Patsy noticed she was wearing a gray wig and granny glasses, and she had loads of pancake makeup on her face. “In my heart,” she said, “I know it was Treva.”

Treva’s arrest did motivate her sisters to start talking to one another for the first time about their own feelings of shame about the past. But they didn’t write Treva either. “We thought that maybe it would be best to just let her continue pretending to believe that she was a teenager,” said Sue. “If she thought she was living in a better place, then so be it.”

The prosecutor offered Treva a plea bargain—a recommendation of two years in prison in return for her admitting who she was. She wouldn’t take the deal. She then fired her court-appointed attorneys when she learned that they were planning to argue that even though she was indeed Treva Throneberry, she had no idea she was committing a crime because she really did believe that she was Brianna Stewart. Treva told the judge that she wanted to exercise her constitutional right—which she apparently had read about in a law book at the library—to defend herself. She said she wanted to convince the jury that she truly was Brianna Stewart. “It is very important for me to clear my name,” she said at a hearing. The judge could not say no. By law, to act as her own counsel Treva only had to demonstrate that she understood the nature of the charges against her and their potential punishment. Her nemesis, prosecutor Michael Kinnie, snarled to the press that Treva was perfectly competent. “She’s graduated from high school at least twice,” he said.

When Muscatel told the judge that he could not find sufficient mental problems to prove her incompetent, the stage was set for a disaster.

Vancouver, Washington—2001

HER TRIAL BEGAN IN MID-NOVEMBER, and each day, Treva shuffled into the courtroom, carrying a stack of law books and notebooks. Although she often kept her hair braided in her usual pigtails, she had traded her overalls for denim skirts that came down to her ankles. Before testimony began, she always smiled at Superior Court judge Robert Harris and said in her little girl’s voice, “Hi.” The esteemed judge was completely discombobulated by Treva. At one point he said, “Hello, Miss Stewart, Miss Throneberry, whatever.”

He had one of her court-appointed attorneys sit beside her to answer any questions she might have about courtroom procedure and other points of law, but Treva seemed perfectly comfortable in her role as defense attorney. “Objection, relevance,” she often called out, beaming at the judge. After several such objections, Kinnie, a serious, bearded fellow, began clenching his fists, trying to control his anger. When an investigator from the prosecutor’s office took the stand and explained the complexities of fingerprint evidence, Treva nodded thoughtfully and, in her cross-examination, asked several rather pointless questions about ridge patterns on particular fingers. It was as if she were back in a high school science class asking a teacher how an experiment worked. Later, when another law enforcement officer told the jury about the way Keili Smitt in Corvallis, Oregon, used numerous aliases, she seemed mystified. “Why would someone come up with so many names?” she asked. “It makes no sense.” This time, she turned and beamed at the jury. The officer just shrugged, staring at her.

Kinnie was so adamant about proving that Brianna really knew her true identity that he called to the stand a woman from a Vancouver convenience store. She said that she had remembered Brianna once coming in with some other teenagers to buy a pack of cigarettes and that Brianna showed an identification card with the name Treva Throneberry. The Evergreen teenagers who had been close to Brianna, however, were convinced that the clerk was lying. They said that Brianna never smoked, and no one could remember going to that store with her.

To further bolster his case, Kinnie had flown in Sharon Gentry, Treva’s foster mother from fifteen years ago, to testify that she had known Treva in 1985, when she was sixteen years old. Gentry’s unexpected appearance led to a moment in the trial that can only be described as heartbreaking. After she answered some perfunctory questions from Kinnie, Treva rose slowly from the defense table, approached the witness, and asked to see some photos that Gentry had brought with her. For the first time Treva seemed ill at ease. She stared at the photo of herself and Gentry on the beach at Port Aransas for spring break, then she stared at a photo of herself with the high school boyfriend from Wichita Falls who had taken her to Six Flags. After a long silence Treva said, “This Treva in these pictures. What was she like?”

Gentry glanced around. She wasn’t sure what to say. “She was a very polite young lady,” she finally said. “She enjoyed church. She enjoyed tennis. She had a wooden tennis racket. She was always very appropriate, very thankful. She always apologized if she hurt my feelings.”

There was another long silence. Treva stared down at her notebook, her eyes blinking. Was it possible that the past was returning—that she was remembering the girl she once was?

“Was Treva smart?” Treva asked.

“Oh, yes. She loved to read and really enjoyed school activities. She made good grades.”

Another silence. “Did she work hard?” Treva asked.

It was clear that Gentry was now struggling to control her emotions. She would later say that she almost stood up at that moment and leaned across the witness box so that she could wrap her arms around Treva. “She worked very hard,” Gentry said. “She tried hard. Treva was a wonderful young woman.”

“Oh,” said Treva. “Thank you.”

As the trial hurried to its conclusion, Treva presented little evidence to counter Kinnie’s case. She attempted to introduce a report from a therapist in Vancouver who had once guessed that Brianna Stewart was about twenty years old, but the judge ruled the report inadmissible. She called her former teachers and counselors to the stand to testify that she had only wanted a Social Security number so that she could continue her schooling. “I wanted to go to college so I could take care of myself, isn’t that right?” she asked her former Evergreen counselor, Greg Merrill. “And not have someone take care of me?”

“All of our conversations were about you being self-sufficient,” Merrill replied stiffly, obviously embarrassed that he had believed Brianna’s story for so long.

In his final argument Kinnie was merciless. He loomed over the jurors and said, “If you feel sorry for her, we don’t give a damn about your tears. That’s not why we’re here.” He then mimicked Treva’s voice, telling the jury that she just wanted to remain a “pampered child” and that she wanted a free financial ride.

For her final argument Treva stood before the jury and read a short speech that she had handwritten in one of her notebooks. “I still say I am Brianna Rebecca Stewart,” she said, polite as always. “I don’t pretend to be anyone else but me.”

It was a slam dunk of a case, of course. The jury quickly found her guilty, and the judge sentenced her to three years in prison. The attorney who had been assisting Treva, Gerry Wear, made a last-minute request for the judge to state for the record whether he thought that Treva was competent to stand trial. “There’s no question in my mind, having spent as much time with her as I have, that she is of the opinion that she is Brianna Stewart,” Wear said. But it was too late. Judge Harris said he wished he could send her to a state hospital for treatment, but his only legal option was prison. The problem with prison in Washington State, he admitted, was that there were limited mental-health services available for inmates. Nor was there any supervision for nonviolent offenders after their release. When Treva completes her sentence, she will be sent out the front door with a little money and perhaps a phone number for a women’s shelter. And without any help, her cross-country odyssey might very well resume.

Treva told the judge she would immediately file an appeal. Before she walked out of the courtroom for the last time, she looked out a window. Rain was beginning to fall outside. With no wind, it came down in a sprinkling whisper, little drops flicking through the last of the maple leaves hanging on the trees. “It’s so unfair,” she said. “It’s so unfair.”

A reporter standing nearby said, “What’s unfair? Are you talking about what happened to you a long time ago?”

She looked at the reporter quizzically, then she gathered her law books and sheets of paper. “My name,” she said, “is Brianna Stewart, and I am nineteen years old.”

As bailiffs led her into an elevator, she said once again, in a much louder voice, to the crowd who had gathered to see her, “I’m nineteen! I’m not guilty of anything except being a teenager!”