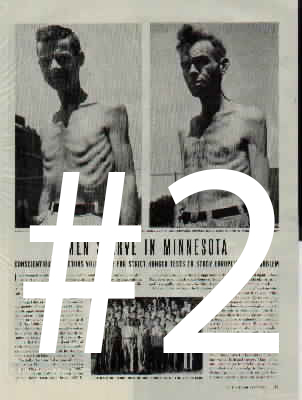

In this NY Times piece we are reminded of the deleterious effects of starvation on the human mind and body. The reporter, Gary Taubes, an expert in the field of bad science, specifically focusing on the lack of rigor in the field of nutrition, uses the Ancel Key’s semi-starvation experiment conducted 1944 as a reminder that starvation diets are not the answer.

“And this was not their only physiological reaction. Their extremities swelled; their hair fell out; wounds healed slowly. They felt continually cold; their metabolism slowed.

More troubling were the psychological effects. The men became depressed, lethargic and irritable. They threw tantrums. They lost their libido. They thought obsessively about food, day and night. The Minnesota researchers called this “semi-starvation neurosis.” Four developed “character neurosis.” Two had breakdowns, one with “weeping, talk of suicide and threats of violence.” He was committed to the psychiatric ward. The “personality deterioration” of the other “culminated in two attempts at self-mutilation.” He nearly detached the tip of one finger and later chopped off three with an ax.

When the period of imposed starvation ended, the subjects were allowed to “refeed.” At first they were allowed to eat more calories, but restricted as to how much. A subset under continued observation was then allowed to eat to satiety, which was surprisingly hard to achieve. The men consumed prodigious amounts of food, up to 10,000 calories a day. They regained weight and fat with remarkable rapidity. After 20 weeks of recovery, they averaged 50 percent more body fat than they had when it began — “post-starvation obesity,” the researchers called it.”

This historic study is than juxaposed to a more recent study, by NIH, widely reported on last week. The more resent study, conduct over less than a week, was spun by the media: “That the subjects lost more fat by restricting dietary fat than they did by restricting the same number of carbohydrate calories. “Scientists (sort of) settle debate on low-carb vs. low-fat diets,” as The Washington Post put it.”

Taubes cautions this is not the whole picture and still doesn’t address the issue of hunger and it’s demonic effects on the human brain.

But the devil in nutrition studies is always in the kind of details that are encapsulated by phrases like “sort of.” Whether the evidence was invaluable, as the N.I.H. claimed, depends on a number of issues. Is the experience of six days relevant to what happens over months, years or a lifetime? There’s little reason to think so. Can humans survive (and if so, for how long) on a diet of 8 percent fat? The Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations has said 15 percent is the lower limit. And then is a diet with about 30 percent carbohydrates sufficiently restricted to be considered a low-carb diet — the N.I.H. diet included blueberry muffins at breakfast, spaghetti at lunch and wraps for dinner.

That humans or any other organism will lose weight if starved sufficiently has never been news. The trick, if such a thing exists, is finding a way to do it without hunger so weight loss can be sustained indefinitely. A selling point for carbohydrate-restricted diets has always been that you can eat to satiety; counting calories is unnecessary, so long as carbohydrates are mostly avoided.

But this advice raises a pair of obvious questions, or at least it should: If people on low-carb diets eat less (the conventional explanation for any loss of fat that ensues), why aren’t they hungry? Where’s the semi-starvation neurosis? And if they don’t eat less, why do they lose weight? It implies a mechanism of weight loss other than caloric deprivation and suggests that the carbohydrates and fats consumed.

Much of the obesity research for the past century has focused on elucidating behavioral techniques that could induce the obese to eat less, tolerate hunger better, and so, by this logic, lose weight. The obesity epidemic suggests that it has failed.

For those who believe that hunger is somehow all in the mind, rather than a powerful biological response to caloric deprivation, it is tempting to wish on them the fate that the goddess Ceres bestowed on King Erysichthon of Thessaly in Greek mythology. She “devised a punishment to rouse men’s pity… to torment him with baleful Hunger.” Erysichthon then eats himself out of castle and kingdom and ultimately dies by feeding, “little by little, on his own body.”