The tension between big pharma’s price fixing and medical advocacy groups, including more and more doctors and politicians, is reaching a boiling point.

This week when Turner Pharmaceuticals raised the price of Daraprim from $13.50 to $750 per pill, overnight people responded. Though its hard to boycott a company that provides a drug you need to survive, social media lit up with calls for change. Hillary Clinton is the first Presidential candidate to lay out her plan for change. The company has since agreed to roll back the price of Daraprim, in part due to Clinton’s tweet which spooked biotech traders into dumping the stock.

The medicine, Daraprim, which has been on the market for 62 years, is the standard of care for a food-borne illness called toxoplasmosis caused by a parasite that can severely affect those with compromised immune systems. Turing purchased the rights to the drug last month and almost immediately raised prices.

Judith Aberg, a spokesperson for the HIV Medicine Association, has calculated that even patients with insurance could wind up paying $150 per pill out of pocket. “This is a tremendous increase,” she told USA Today.

The New York Times reported that Alberg’s group and the Infectious Diseases Society of America wrote in a joint letter to Turing earlier this month complaining that the price increase is “unjustifiable for the medically vulnerable patient population” and “unsustainable for the health care system.”

The news even got the attention of Democratic presidential candidate Hillary Rodham Clinton, who called the pricing “outrageous” and promised that she had a plan to take on the issue. Clinton is scheduled to unveil a highly anticipated drug pricing proposal Tuesday.

“The enormous, overnight price increase for Daraprim is just the latest in a long list of skyrocketing price increases for certain critical medications,” Sanders and Cummings said. “Americans should not have to live in fear that they will die or go bankrupt because they cannot afford to take the life-saving medication they need.”

Turing spokesman Craig Rothenberg has said the company will use the money from the sales to further research treatments for toxoplasmosis, which he said has long been neglected. He also said the firm had plans to invest in marketing and education tools to raise awareness of the disease — a reasonable and reasoned answer, but one that has been unsatisfactory for many.

Turing’s price increase is not an isolated example. While most of the attention on pharmaceutical prices has been on new drugs for diseases like cancer, hepatitis C and high cholesterol, there is also growing concern about huge price increases on older drugs, some of them generic, that have long been mainstays of treatment.

Although some price increases have been caused by shortages, others have resulted from a business strategy of buying old neglected drugs and turning them into high-priced “specialty drugs.”

Cycloserine, a drug used to treat dangerous multidrug-resistant tuberculosis, was just increased in price to $10,800 for 30 pills from $500 after its acquisition by Rodelis Therapeutics. Scott Spencer, general manager of Rodelis, said the company needed to invest to make sure the supply of the drug remained reliable. He said the company provided the drug free to certain needy patients.

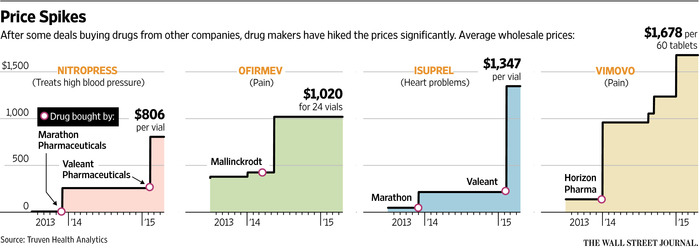

In August, two members of Congress investigating generic drug price increases wrote to Valeant Pharmaceuticals after that company acquired two heart drugs, Isuprel and Nitropress, from Marathon Pharmaceuticals and promptly raised their prices by 525 percent and 212 percent respectively. Marathon had acquired the drugs from another company in 2013 and had quintupled their prices, according to the lawmakers, Senator Bernie Sanders, the Vermont independent who is seeking the Democratic nomination for president, and Representative Elijah E. Cummings, Democrat of Maryland.

Doxycycline, an antibiotic, went from $20 a bottle in October 2013 to $1,849 by April 2014, according to the two lawmakers.

*****

Martin Shkreli, the founder and chief executive of Turing, said that the drug is so rarely used that the impact on the health system would be minuscule and that Turing would use the money it earns to develop better treatments for toxoplasmosis, with fewer side effects.

“This isn’t the greedy drug company trying to gouge patients, it is us trying to stay in business,” Mr. Shkreli said. He said that many patients use the drug for far less than a year and that the price was now more in line with those of other drugs for rare diseases.

“This is still one of the smallest pharmaceutical products in the world,” he said. “It really doesn’t make sense to get any criticism for this.”

This is not the first time the 32-year-old Mr. Shkreli, who has a reputation for both brilliance and brashness, has been the center of controversy. He started MSMB Capital, a hedge fund company, in his 20s and drew attention for urging the Food and Drug Administration not to approve certain drugs made by companies whose stock he was shorting.

We understand that pharmaceutical companies need to spend a lot of money researching potential drugs, running trials and so forth. We are not interested in discouraging medical discovery. However, when a drug has been around for decades, and is widely used, the drug has likely paid for itself more than once over. This now becomes a situation that feels like something out of a bad futuristic movie. Only the rich can afford their medicine, with a larger and larger aging population and more and more drugs raising prices this problem seems to be on the brink of disaster.

Here’s one woman’s experience with an overnight increase in progestrine, a drug she needs to help prevent the premature birth of her child.

From the Common Health Blog on NPR

Every week, my husband injects me with 250 mg (1 ml) of 17 alpha-hydroxyprogesterone caproate (“progesterone” for short). Leaving aside what this does to an otherwise tender and loving marriage, these injections have been found to significantly lower the risk of preterm birth.

Two weeks ago, my insurance co-pay for progesterone went from $5.50 per dose to $70 per dose. Just like that. For those without insurance (or with a deductible), the medication went from $32.50 per dose, according to my local compounding pharmacy, to…wait for it…$833 per dose, according to the new pharmacy my insurer is now requiring me to use.

$833. Per. Dose.

Pricing varies somewhat across pharmacies and insurers, but not enough to make this price change any less breathtaking. In fact, the drug’s list price is $690 per dose.

The 12-fold leap in my co-pay sent an epic shock through my (natural and synthetic) hormone-laden system. I immediately called both pharmacies, my insurer, and my doctor, and started digging around online. I soon learned that the price increase came from a new requirement to buy expensive brand-name progesterone, instead of the affordable compounded version I had been getting. A disturbing picture came into focus.

In 2011, a company called KV Pharmaceutical received FDA approval for its own brand-name version of progesterone, Makena. The approval came with seven years of market exclusivity. Monopoly in hand, KV set a price of $1,500 per dose for Makena, compared to $10-$20 for compounded versions. The public noticed, and got mad. The company responded by cutting Makena’s price in half, but it still got a well-deserved public scolding. Patients, medical organizations and members of Congress issued statements of protest, some of which were covered by this very blog at the time. The March of Dimes, which had championed FDA approval of Makena, broke off its close relationship with KV and its subsidiary, Ther-Rx, when the price was made public. For more, here’s an overview of the saga.

Two senators called for a federal antitrust investigation. Senator Sherrod Brown (D-OH) did not mince words:

“Price-gouging is never acceptable, particularly not when it undermines public health and fleeces taxpayers.”

Sen. Brown was not alone in pointing out that KV Pharmaceutical gained FDA approval for Makena thanks in part to millions of dollars of help from taxpayer-funded National Institutes of Health studies.

Amid the controversy, the FDA decided to allow compounding pharmacies to continue dispensing their own versions as well, preserving progesterone access for all in need. KV Pharmaceutical did not appreciate this: It sued the FDA to compel it to shut down the compounders. The suit didn’t save them from bankruptcy, and a month after their filing the suit was dismissed anyway. Suffice it to say that 2012 was not a great year for KV.

But things have since turned around for the company. By early 2014, KV had emerged from bankruptcy, and attitudes and laws regarding compounders had changed (in no small part due to this tragic outbreak). This past January, a U.S. Court of Appeals in Washington, D.C., reversed the dismissal. In other words, KV is again actively suing the FDA to shut down compounders and secure its monopoly on progesterone.

But a decision has not yet been made, so why did my price skyrocket? It took quite a few inquiries to find out, and the answer was not what I expected, nor does it feel complete.

My inability to acquire compounded progesterone doesn’t seem to be due to the lawsuit, but rather to the Drug Quality and Security Act, signed into law last November. The International Academy of Compounding Pharmacists (IACP) told me they and their members have interpreted the new law to mean that the FDA prohibits compounders from legally preparing progesterone injections unless the dosing or method of delivery prescribed by a physician are different from Makena.

So, unless I can convince my doctor that I have a medical need for, let’s say, mint-scented progesterone delivered in half-doses by purple needles, I have to go with Makena. Nothing wrong with that…except for the price.

Now’s probably a good time to remind you that I’m on bed rest, with an abundance of time on my hands. I asked the FDA what they thought of the IACP’s interpretation, and here’s what I got:

The agency cannot speculate on why a compounder would have discontinued compounding hydroxyprogesterone caproate.

Hmmm, FDA, I’m no expert, but maybe it was those “guidance documents” for compounders you released just days after the new law went into effect? But why did my compounder take months to act? Did lawmakers and the FDA realize the DQSA would give KV what it is suing for? I don’t know. But I’m keen to find out if someone has a clear answer. Anyway, moving on…

With just two weeks’ worth of compounded progesterone left, I called Makena Care Connection, set up by KV to help a subset of women afford their pricey meds. They promptly sent me a free vial of five doses. Thanks, guys, that finishes off my treatment. But what about everyone else? That’s not a rhetorical question: My CommonHealth editor, Rachel Zimmerman, asked KV directly. To hear them tell it, $690 a dose is just a formality. Here’s part of the statement they sent over:

The price to insurers varies depending on the level of rebates the company pays to them, which results in a price considerably less than the list price of $690 per dose. State Medicaid programs, as an example, receive a deeply discounted price through a combination of statutory rebates and additional rebates offered by the company…

Our company has a financial assistance program in place for Makena with no upper income limits to qualify for assistance. This financial assistance applies to copays and deductibles. We also provide the drug at no cost to uninsured women.

Well, $70 a dose is certainly “considerably less” than $690. But it’s also considerably more than $5.50, and I doubt my compounding pharmacy cared about me enough to price it at a loss. Plus, $70 is just my co-pay; my insurer is likely paying much more. I know little about the economics of pharmaceuticals and insurers, but I think it’s fair to assume that added cost will make its way into my premium at some point. (The numbers junkies among you will appreciate this New England Journal of Medicine article from 2011.)

As for the “financial assistance program,” it seems to work great for women like me who are fortunate enough to have learned about it, navigated the paperwork and the phone calls with the help of a competent and responsive medical office, and met the somewhat opaque eligibility criteria. Let’s not assume all women get to have a high-risk pregnancy in such favorable conditions.

Don’t get me wrong: I understand the upsides of brand-name progesterone. A good manufacturer can bring uniformity and improved safety to a drug that was being prepared by hundreds of different compounding pharmacies. I’ll try to set aside the fact that the FDA shut down KV five years ago for “making, marketing and distributing adulterated and unapproved drugs.” I’ll also try to set aside research by the FDA and others, and statements by major medical groups indicating the compounders were doing fine (with one exception: the pharmacy where my insurer now requires me to fill my prescription).

Here’s how it looks to me and many others: KV has taken an affordable, effective drug that was in use for decades, a drug they did not invent, and is exploiting it shamelessly. To me, it doesn’t really matter who’s to blame for removing affordable alternatives, when all we’re left with is an effective drug at an insane price. My doctor’s office told me that they are scrambling to help women deal with this. Women who can’t afford Makena are faced with finding alternatives, shortening their course of treatment, or going entirely without. I can tell you firsthand that changing a treatment mid-course when your baby’s well-being is on the line is terrifying.

If KV is indeed bringing value, they deserve fair compensation. But raising prices astronomically when hundreds of thousands of women, babies and their families depend on it? No. Preterm births have huge emotional, physical and financial costs. What KV is doing with Makena reaches beyond issues of legality into morality.

I am well aware that unfair pricing happens throughout the U.S. health care system. burdening patients, providers, private and public insurers and taxpayers. But this one landed in my corner, and I’m speaking out. Don’t mess with a woman on bed rest. Time is on my side… until the progesterone runs out.

Rekha Murthy lives in Arlington with her husband and 2-year-old daughter. She is getting more pregnant by the day.

Here are the main tenets of Hillary Clinton’s plan to stop pharmaceutical price gouging:

1. Requiring Drug Companies Like Turing to Spend a Minimum on Research and Development, not Profits and Marketing

You might be familiar with a provision of the Affordable Care Act that prevented your insurance company from spending above a certain amount on overhead, such as administrative costs, profits, and advertising.

Hillary’s plan would apply a version of this rule to drug companies, creating a mechanism where Turing would have to spend a minimum on Research and Development. In requiring companies like Turing to invest more of their revenues or pay rebates to support research rather than keep them as profits, it lessens the incentive for these companies to chase ever-higher earnings through price gouging. It also makes more funds available for research that could lead to the development of competitor drugs.

2. Requiring drug companies to justify price increases

Okay, this one seems overly simple, but it absolutely works.

Like Turing, many companies have entered the biotech industry operating on a deliberate strategy of purchasing old drugs, driving up the price, and calling them “specialty drugs.”

From The Times:

Cycloserine, a drug used to treat dangerous multidrug-resistant tuberculosis, was just increased in price to $10,800 for 30 pills from $500 after its acquisition by Rodelis Therapeutics

Well just yesterday, Rodelis was forced to return the drug to its original owner after, essentially, a round of public shaming around their price hikes.

The plan invests in private organizations that do research on pharmaceutical products who serve as a second opinion for consumers (and payers).

By making clearer what a drug actually costs to produce, this allows insurance companies — and under Clinton’s plan, Medicare — to negotiate for lower rates, while giving consumers a sense of what is a ridiculous asking price and what isn’t. And it will help inform additional regulatory and anti-competitiveness enforcement at the state and federal level to prevent price-gouging in cases like these.

3. Encouraging More Competition

Another proposal in Clinton’s plan would incentivize more competition in the market for these drugs. When drugs are the only ones on the market, with no competition to keep the price down, drug companies often charge excessive prices. Sound familiar? With more drugs on the market, companies like Turing wouldn’t be able to inflate prices without concern for competition.

In addition to things like lowering the exclusivity period on biologics from 12 to 7 years, it would also encourage the FDA to prioritize approving drugs that have limited competition. In addition, it would fund the FDA’s Office of Generic Drugs to help clear out the multi-year backlog that is keeping competitors off the market.

4. Out of Pocket Payment Limits

While the other three proposals all address costs that drug companies can charge, this plank of her plan would focus on limiting the amount that Americans would have to pay out of pocket. Her plan would require health insurance plans to place a monthly limit of $250 on covered out-of-pocket prescription drug costs.

Following the example of states like Maine and California, this would lift a huge burden for patients with chronic or serious health conditions and would ensure Americans can get the care their doctors prescribe. In fact — up to a million Americans could benefit from this proposal every year.

Making Prescription Drugs Affordable For Everyone

At the end of the day, Americans are being squeezed by rising drug costs, while the pharmaceutical industry earns billions in profits. Our biotechnology and pharmaceutical industries have provided many new and lifesaving treatments, and Clinton’s plan will support true innovation. But it will also crack down on bad actors who exploit patients without doing the hard work of developing new treatment. While Turing is only the most recent — and prominent — example of the rampant profiteering made off of Americans at their most vulnerable, we need to make sure that taxpayer support goes toward real innovation and R&D, not excessive profits and marketing expenses in excess of research budgets.

Hillary Clinton is fighting to make sure that American families and seniors aren’t held over the barrel by an industry focuses on profits, not patients. And while she won’t be able to stop every bad actor like Martin Shkreli, there’s a lot she can do to make the pharmaceutical industry fairer for every American — and that’s exactly what she intends to do.