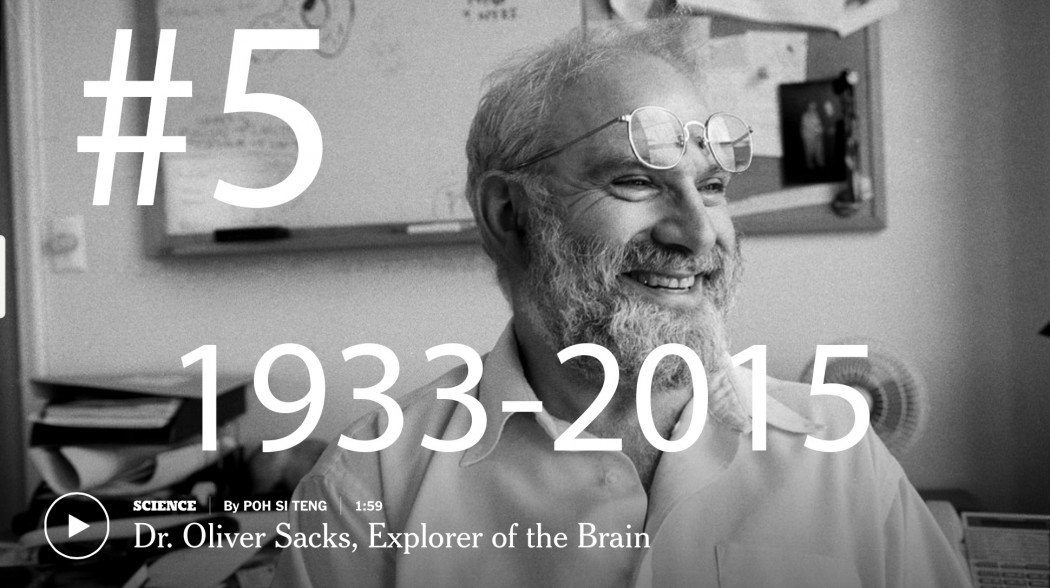

Oliver Sack, the neurologist, died this week at his home in New York. Sacks who’s widely known for his work on best sellers like, Awakenings, The Man Who Mistook His Wife for a Hat and others, was a profound storyteller. He took care to understand his patients and was able to retell their hardships in humorous ways, which encouraged us to drop the stigma against those with neurological disordered. Sacks was a regular commentator on one of our favorite programs, Radio Lab. After publicly announcing his Cancer had metastasized, Sacks said he wouldn’t do anymore interviews, but he agreed to have one final conversation with Radio Lab host Robert Krulwich here it is: Radiolab

Sacks talks about the sadness he felt learning his eye cancer was now in his liver. Then he talks about his own experience of delirium, he’s conducting experiments on himself while being treated. He was a consummate student, always learning. This Radio Lab piece is an intimate conversation between two old friends.

In his final interview Sacks talks about love for the first time publicly. It turns out this incredibly sensitive doctor known for being a good listener, and a source of great comfort to his patients, was not looked after with the same tenderness in his own early life. His deeply religious mother rejected him after learning he was gay, an experience that left him isolated and lonely.

Here’s Sack last piece in the New York Times, Sabbath

I gradually became more indifferent to the beliefs and habits of my parents, though there was no particular point of rupture until I was 18. It was then that my father, inquiring into my sexual feelings, compelled me to admit that I liked boys.

“I haven’t done anything,” I said, “it’s just a feeling — but don’t tell Ma, she won’t be able to take it.”

He did tell her, and the next morning she came down with a look of horror on her face, and shrieked at me: “You are an abomination. I wish you had never been born.” (She was no doubt thinking of the verse in Leviticus that read, “If a man also lie with mankind, as he lieth with a woman, both of them have committed an abomination: They shall surely be put to death; their blood shall be upon them.”)

The matter was never mentioned again, but her harsh words made me hate religion’s capacity for bigotry and cruelty.

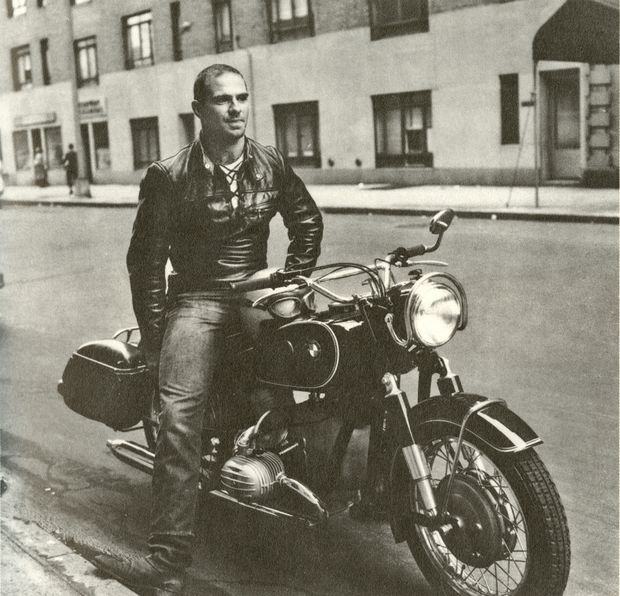

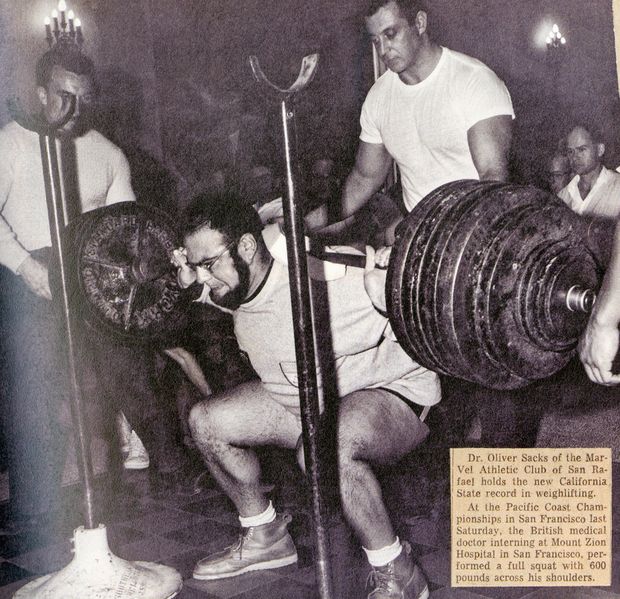

After I qualified as a doctor in 1960, I removed myself abruptly from England and what family and community I had there, and went to the New World, where I knew nobody. When I moved to Los Angeles, I found a sort of community among the weight lifters on Muscle Beach, and with my fellow neurology residents at U.C.L.A., but I craved some deeper connection — “meaning” — in my life, and it was the absence of this, I think, that drew me into near-suicidal addiction to amphetamines in the 1960s.

Recovery started, slowly, as I found meaningful work in New York, in a chronic care hospital in the Bronx (the “Mount Carmel” I wrote about in “Awakenings”). I was fascinated by my patients there, cared for them deeply, and felt something of a mission to tell their stories — stories of situations virtually unknown, almost unimaginable, to the general public and, indeed, to many of my colleagues. I had discovered my vocation, and this I pursued doggedly, single-mindedly, with little encouragement from my colleagues. Almost unconsciously, I became a storyteller at a time when medical narrative was almost extinct. This did not dissuade me, for I felt my roots lay in the great neurological case histories of the 19th century (and I was encouraged here by the great Russian neuropsychologist A. R. Luria). It was a lonely but deeply satisfying, almost monkish existence that I was to lead for many years.

I had felt a little fearful visiting my Orthodox family with my lover, Billy — my mother’s words still echoed in my mind — but Billy, too, was warmly received. How profoundly attitudes had changed, even among the Orthodox, was made clear by Robert John when he invited Billy and me to join him and his family at their opening Sabbath meal.

The peace of the Sabbath, of a stopped world, a time outside time, was palpable, infused everything, and I found myself drenched with a wistfulness, something akin to nostalgia, wondering what if: What if A and B and C had been different? What sort of person might I have been? What sort of a life might I have lived?

In December 2014, I completed my memoir, “On the Move,” and gave the manuscript to my publisher, not dreaming that days later I would learn I had metastatic cancer, coming from the melanoma I had in my eye nine years earlier. I am glad I was able to complete my memoir without knowing this, and that I had been able, for the first time in my life, to make a full and frank declaration of my sexuality, facing the world openly, with no more guilty secrets locked up inside me.

In February, I felt I had to be equally open about my cancer — and facing death. I was, in fact, in the hospital when my essay on this, “My Own Life,” was published in this newspaper. In July I wrote another piece for the paper, “My Periodic Table,” in which the physical cosmos, and the elements I loved, took on lives of their own.

And now, weak, short of breath, my once-firm muscles melted away by cancer, I find my thoughts, increasingly, not on the supernatural or spiritual, but on what is meant by living a good and worthwhile life — achieving a sense of peace within oneself. I find my thoughts drifting to the Sabbath, the day of rest, the seventh day of the week, and perhaps the seventh day of one’s life as well, when one can feel that one’s work is done, and one may, in good conscience, rest.

Here is an obit from a colleague of Sack’s at The New Yorker

A great deal will be said in the coming days about Oliver’s unique literary output—masterful books including “An Anthropologist on Mars,” “Awakenings,” and “The Man Who Mistook His Wife for a Hat.” But we should remember that he also embodied in his medical practice a kind of ideal approach—creative, sensitive, and large-hearted—to his many patients. He was an extraordinary and exemplary doctor.

Neurology is often depicted as a discipline of great detachment. Sacks, who was eighty-two when he died, trained in the field before the advent of the CT scan and the MRI. He learned to observe his patients in extreme detail, calling on his professional training and uncanny perception to make meticulous analyses of motor strength, reflexes, sensation, and mental status; in doing so, he arrived at a diagnosis that might locate a lesion within the anatomy of the brain or spinal cord. And yet, because medical technology had only gone so far in those days, once this intellectual exercise was completed, there was often very little that could be done to ameliorate most neurological maladies.

Sacks showed that it was possible to overcome this limited perspective. He questioned absolutist categories of normal and abnormal, healthy and debilitated. He did not ignore or romanticize the suffering of the individual. He sought to locate not just the affliction but a core of creative possibility and a reservoir of potential that was untapped in the patient. There was the case history, for instance, of a color-blind painter who lost all perception of color but discovered that he could capture the nuances of forms and shapes in hues of black and gray with great mastery.

As both a physician and as a writer, Oliver’s two great themes were identity and adaptation. Illness, he made plain, need not rob us of our essential selves—and this was something he exemplified in his final months, as a he continued to write remarkable essays even as cancer began to sap his strength and overwhelm him. Sacks understood our frequent ability to adapt, and emphasized that the capacity for someone to adapt to a particular condition—amnesia, blindness, deafness, migraines, phantom-limb syndrome, Asperger’s syndrome, and countless other conditions—cannot be known from the outset. These concepts grew from his study of zoology and evolution at Oxford. He similarly saw in medicine a great diversity among individual patients, and the inherent uncertainty of the outcome of a particular disorder. These unknowns gave hope to patients guided by the right doctor—a hope he captured in his description, in “Awakenings,” of catatonic-seeming encephalitis patients at Beth Abraham Hospital, in the Bronx, who had been written off as “locked in” and then revived, at least provisionally, by drugs like L-Dopa.

Sacks was a contrarian who refused to compromise this approach to the sick and the suffering. He resisted the powerful current of modern practice that seeks the generic. He rejected a monolithic mindset, and retrieved the individual from the obscuring blanket of statistics. This put him outside of the academy, exiled to chronic-care institutions. Through his writing, Sacks ultimately received recognition for advancing a unique form of clinical scholarship that was largely abandoned: the study of the single person within the context of his own life. Ever the acute observer, his case histories confirmed that under a single diagnostic term was a spectrum of human biology. No two patients are ever the same, he emphasized. When examining patients on the autistic spectrum, for example, he highlighted, and informed the public about, individuals with the capacity to draw precisely from memory, the capacity to make calculations nearly at the speed of a computer, or the ability to listen to a piece of music and reproduce it on the piano.

Sacks made house calls, not only in California and New York where he practiced, but globally, visiting Dr. “Bennet,” a surgeon with Tourette’s syndrome in rural Canada or the autistic artist Stephen Wiltshire on a tour of Europe. In these visits, he practiced what might be called the medicine of friendship, showing genuine interest and respect to people who are often shunned. This was the therapeutic intervention when neurology lacked effective pills or procedures.

This did not mean Sacks was a Luddite. He was an avid reader of scientific journals, fascinated by scientific advancements in imaging the nervous system at work. He engaged in dialogue with Nobel laureates and lab scientists about the nature of consciousness, providing what they lacked—the insights of a naturalist, a field worker.

Sacks also embodied an attribute that can be lost after people become famous: a boundless generosity of spirit. He encouraged young doctors and scientists to record their experiences and communicate them in prose, celebrating their endeavors rather than seeing them as a form of competition or threat. I believe his intense curiosity and boundless energy moved him to want to learn from the succeeding generation, as great teachers do.

Over the past years, Oliver revealed a part of his life that was once considered a debility and disorder—his sexual orientation. The demeaning of this part of his person, he believed, was the cause for his descent into amphetamine abuse. Drugs may well have killed him decades ago, before his contributions to medicine and writing. It was clinical work, caring for others with competence and compassion, that proved therapeutic for the doctor, giving him the strength to break the powerful grip of drug use. After decades of celibacy, Oliver shared the last eight years of his life with the writer Billy Hayes.

In May, after I had reviewed “On the Move: A Life,” his autobiography, he sent me a letter about what he wanted to accomplish in the time left to him. “In whatever time remains,” he aimed to “pull together another book of case histories–some large … some small, even miniature.” Every dimension of the patient was meaningful in his thinking.