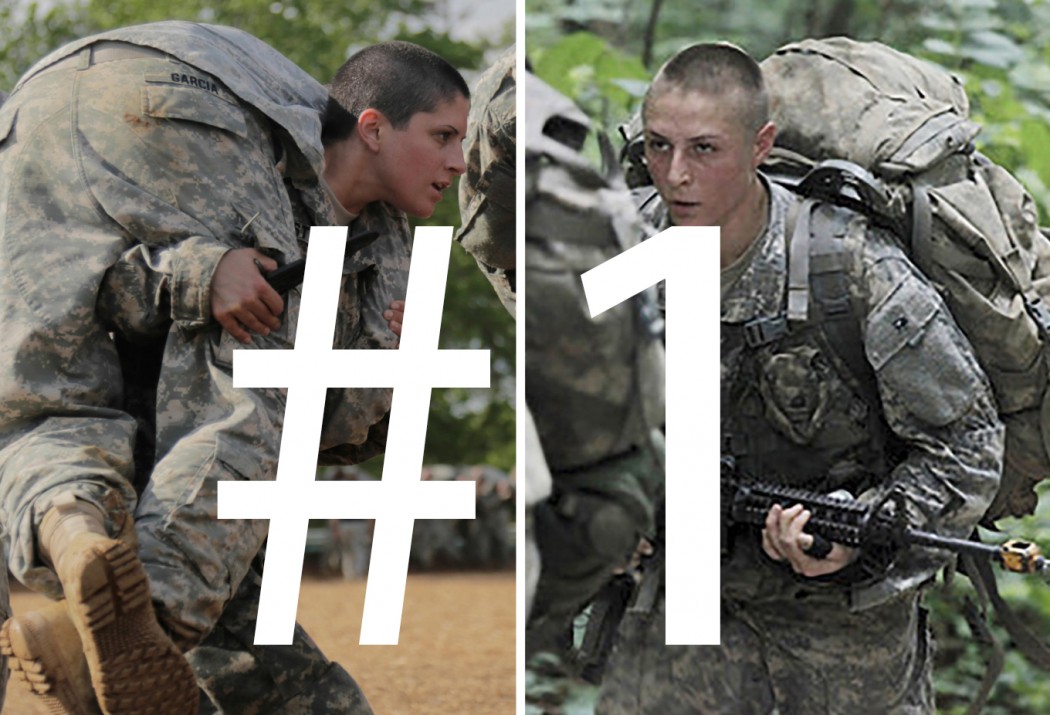

Briefing: Though the first female graduates passed the course, the question remains will they be allowed to serve as Rangers?

Two women completed the notoriously tough Army Ranger’s program. Capt. Kristen Griest and First Lt. Shaye Haver were held to the same standards, no exceptions made, as their male counterparts. This is the first time in US History that women were permitted to try.

“Although Haver and Griest are now Ranger-qualified, no women are eligible for the elite regiment, although officials say it is among special operations units likely to be opened to women eventually.

Griest, 26, is a military police officer and has served one tour in Afghanistan. Haver, 25, is a pilot of Apache helicopters. Both are graduates of the U.S. Military Academy at West Point. Of 19 women who began the Ranger course, Haver and Griest are the only two to finish so far; one is repeating a prior phase of training in hopes of graduating soon.”

The Department of Defense requires all branches of the military open up all positions to women or file for an exemption by January 2016. The Navy Seals are said to be currently in the process of opening Seal training. The Marines, the least female populated branch of military is the only one believed to be moving towards filing for an exemption.

Here’s an oped from the Chicago Tribune on this topic:

The Pentagon plans to open all ground combat positions to women who qualify, removing a significant barrier to full integration of the sexes. But there’s a catch: By the end of September, the Army, Navy, Air Force and Marines are due to recommend whether to accept this new reality (women in the infantry, for example, or the commandos) or seek exceptions and keep some jobs, or many, closed.

It’s time — if not overdue — to give women the same opportunities as men to qualify for direct battlefield roles.

Gender stereotypes are falling in the armed forces, though at a slower pace than in society overall. Women fly fighter jets in the Air Force, serve as gunners on Humvees in the Army and on submarines in the Navy, but they are still not allowed to serve in many ground combat positions. The concerns, and discrimination, once were overarching: that women weren’t tough enough or strong enough to fight, or protect themselves, or others. They were distractions, likely to destroy “unit cohesion.” Or upset the folks at home when they were killed in action or taken prisoner. Those arguments stood for decades.

But women have shown through their expanded participation how capable they are. They serve alongside men, they lead men, and they stand ready to make the same sacrifices. The issue should no longer be stereotyping or sexism. The issue should be task-specific: Are there jobs women cannot physically perform?

Women and men are physically different. The most obvious variable is brute strength: Women, generally speaking, have less upper-body power than men, which can pose a challenge or risk when lifting an artillery shell, or moving a heavy truck tire. But not all male soldiers are brutes, either.

The military understands this. One question is whether leadership is willing to allow women to try, and perhaps fail, to make the cut in certain jobs. The companion question is whether the military is willing to see women accept greater challenges — and succeed.

The Navy sounds like it’s ready to open its elite SEAL teams to women who can pass the grueling test. The Army seems ready to break down a lot of doors. It’s the Marines who are struggling. The Marines temporarily opened an 86-day Infantry Officer Course to women, but only a small number took up the challenge. None made it to graduation. Of all the services, women constitute the smallest number in the Marines — about 8 percent. More than 14 percent of the Army is female. Is the issue with the Marines that expectations are more demanding, even than for Army Rangers? Senior leaders will have to prove that. Otherwise we might conclude women are less welcome in the Marines.

The number of women who ultimately serve in some specialized combat jobs may never be large. Perhaps the number will grow over time. What’s important is to allow female service members like Griest and Haver to answer the call of duty as they choose, and then prove themselves equally capable to men.

Otherwise we’ll never have more scenes like last week’s Ranger commencement, and never hear male comrades like 2nd Lt. Michael Janowski say of female comrades like Haver: “No matter how bad she was hurting, she was always the first to volunteer to grab more weight.” In an assessment of his fellow Ranger, Janowski said: “I wrote about how I would trust her with my life.”

Before Haver and Griest graduated, Military.com did this piece on women entering the training, this provides an overview of the varying attitudes and one candidates expectations:

Before she started working as a platoon trainer, Smith didn’t think women belonged in infantry positions. But in training other men and women, she has seen women who are just as skilled, just as strong and just as smart as men. Now she feels that women and men should have the same opportunities in the military — so long as they are held to the same standard. Aside from the mental and physical exhaustion that awaits in the Ranger training program, she says she now feels pressure to succeed on behalf of women.

In Ranger School, candidates are deprived of sleep and food. Along with time at Fort Benning, the training takes them to the mountains of North Georgia and the swamps of Florida. Only about half of candidates complete successfully. It’s so intense that some have died during the program.

“I think it will be the challenge of my life,” Smith said. “I’m all about new experiences and this is going to be a new experience.”