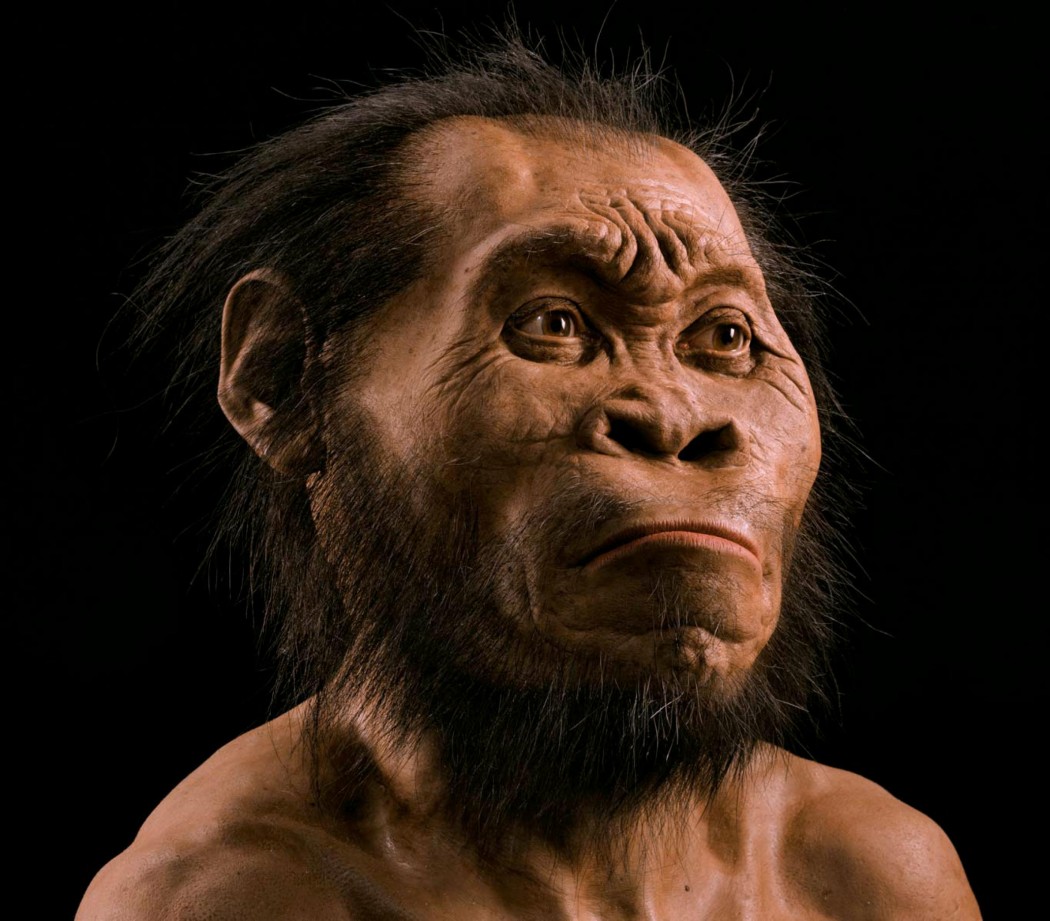

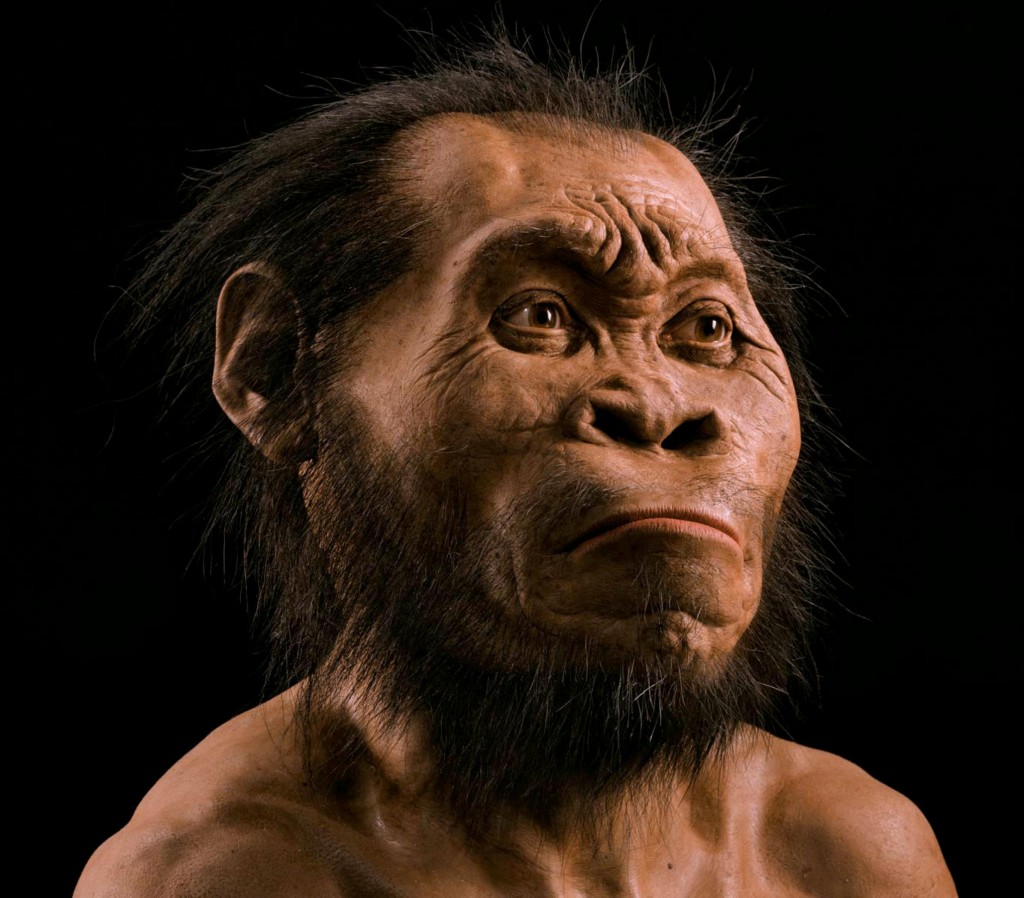

While primitive in some respects, the face, skull, and teeth show enough modern features to justify H. naledi’s placement in the genus Homo. Artist Gurche spent some 700 hours reconstructing the head from bone scans, using bear fur for hair.

A trove of bones hidden deep within a South African cave represents a new species of human ancestor, scientists announced Thursday in the journal eLife. Homo naledi, as they call it, appears very primitive in some respects—it had a tiny brain, for instance, and apelike shoulders for climbing. But in other ways it looks remarkably like modern humans. When did it live? Where does it fit in the human family tree? And how did its bones get into the deepest hidden chamber of the cave—could such a primitive creature have been disposing of its dead intentionally?

This is the story of one of the greatest fossil discoveries of the past half century, and of what it might mean for our understanding of human evolution.

Sunlight falls through the entrance of Rising Star cave, near Johannesburg. A remote chamber has yielded hundreds of fossil bones—so far. Says anthropologist Marina Elliott, seated, “We have literally just scratched the surface.”

Chance Favors the Slender Caver

Two years ago, a pair of recreational cavers entered a cave called Rising Star, some 30 miles northwest of Johannesburg. Rising Star has been a popular draw for cavers since the 1960s, and its filigree of channels and caverns is well mapped. Steven Tucker and Rick Hunter were hoping to find some less trodden passage.

In the back of their minds was another mission. In the first half of the 20th century, this region of South Africa produced so many fossils of our early ancestors that it later became known as the Cradle of Humankind. Though the heyday of fossil hunting there was long past, the cavers knew that a scientist in Johannesburg was looking for bones. The odds of happening upon something were remote. But you never know.

Deep in the cave, Tucker and Hunter worked their way through a constriction called Superman’s Crawl—because most people can fit through only by holding one arm tightly against the body and extending the other above the head, like the Man of Steel in flight. Crossing a large chamber, they climbed a jagged wall of rock called the Dragon’s Back. At the top they found themselves in a pretty little cavity decorated with stalactites. Hunter got out his video camera, and to remove himself from the frame, Tucker eased himself into a fissure in the cave floor. His foot found a finger of rock, then another below it, then—empty space. Dropping down, he found himself in a narrow, vertical chute, in some places less than eight inches wide. He called to Hunter to follow him. Both men have hyper-slender frames, all bone and wiry muscle. Had their torsos been just a little bigger, they would not have fit in the chute, and what is arguably the most astonishing human fossil discovery in half a century—and undoubtedly the most perplexing—would not have occurred.

After Lucy, a Mystery

Lee Berger, the paleoanthropologist who had asked cavers to keep an eye out for fossils, is a big-boned American with a high forehead, a flushed face, and cheeks that flare out broadly when he smiles, which is a lot of the time. His unquenchable optimism has proved essential to his professional life. By the early 1990s, when Berger got a job at the University of the Witwatersrand (“Wits”) and had begun to hunt for fossils, the spotlight in human evolution had long since shifted to the Great Rift Valley of East Africa.

Most researchers regarded South Africa as an interesting sidebar to the story of human evolution but not the main plot. Berger was determined to prove them wrong. But for almost 20 years, the relatively insignificant finds he made seemed only to underscore how little South Africa had left to offer.

What he most wanted to find were fossils that could shed light on the primary outstanding mystery in human evolution: the origin of our genus, Homo, between two million and three million years ago. On the far side of that divide are the apelike australopithecines, epitomized by Australopithecus afarensis and its most famous representative, Lucy, a skeleton discovered in Ethiopia in 1974. On the near side is Homo erectus, a tool-wielding, fire-making, globe-trotting species with a big brain and body proportions much like ours. Within that murky million-year gap, a bipedal animal was transformed into a nascent human being, a creature not just adapted to its environment but able to apply its mind to master it. How did that revolution happen?

The fossil record is frustratingly ambiguous. Slightly older than H. erectus is a species called Homo habilis, or “handy man”—so named by Louis Leakey and his colleagues in 1964 because they believed it responsible for the stone tools they were finding at Olduvai Gorge in Tanzania. In the 1970s teams led by Louis’s son Richard found more H. habilis specimens in Kenya, and ever since, the species has provided a shaky base for the human family tree, keeping it rooted in East Africa. Before H. habilis the human story goes dark, with just a few fossil fragments of Homo too sketchy to warrant a species name. As one scientist put it, they would easily fit in a shoe box, and you’d still have room for the shoes.

Then, in 2008, he made a truly important discovery. While searching in a place later called Malapa, some ten miles from Rising Star, he and his nine-year-old son, Matthew, found some hominin fossils poking out of hunks of dolomite.

Over the next year Berger’s team painstakingly chipped two nearly complete skeletons out of the rock. Dated to about two million years ago, they were the first major finds from South Africa published in decades. (An even more complete skeleton found earlier has yet to be described.) In most respects they were very primitive, but there were some oddly modern traits too.

Berger decided the skeletons were a new species of australopithecine, which he named Australopithecus sediba. But he also claimed they were “the Rosetta stone” to the origins of Homo. Though the doyens of paleoanthropology credited him with a “jaw-dropping” find, most dismissed his interpretation of it. A. sediba was too young, too weird, and not in the right place to be ancestral to Homo: It wasn’t one of us. In another sense, neither was Berger. Since then, prominent researchers have published papers on early Homo that didn’t even mention him or his find.

Berger shook off the rejection and got back to work—there were additional skeletons from Malapa to occupy him, still encased in limestone blocks in his lab. Then one night, Pedro Boshoff, a caver and geologist Berger had hired to look for fossils, knocked on his door. With him was Steven Tucker. Berger took one look at the pictures they showed him from Rising Star and realized that Malapa was going to have to take a backseat.

Skinny Individuals Wanted

After contorting themselves 40 feet down the narrow chute in the Rising Star cave, Tucker and Rick Hunter had dropped into another pretty chamber, with a cascade of white flowstones in one corner. A passageway led into a larger cavity, about 30 feet long and only a few feet wide, its walls and ceiling a bewilderment of calcite gnarls and jutting flowstone fingers. But it was what was on the floor that drew the two men’s attention. There were bones everywhere. The cavers first thought they must be modern. They weren’t stone heavy, like most fossils, nor were they encased in stone—they were just lying about on the surface, as if someone had tossed them in. They noticed a piece of a lower jaw, with teeth intact; it looked human.

Berger could see from the photos that the bones did not belong to a modern human being. Certain features, especially those of the jawbone and teeth, were far too primitive. The photos showed more bones waiting to be found; Berger could make out the outline of a partly buried cranium. It seemed likely that the remains represented much of a complete skeleton. He was dumbfounded. In the early hominin fossil record, the number of mostly complete skeletons, including his two from Malapa, could be counted on one hand. And now this. But what was this? How old was it? And how did it get into that cave?